Step into the world of the Ascaris roundworm. Learn how it grows, spreads, what it looks like, and how to spot it–all through one worm’s journey.

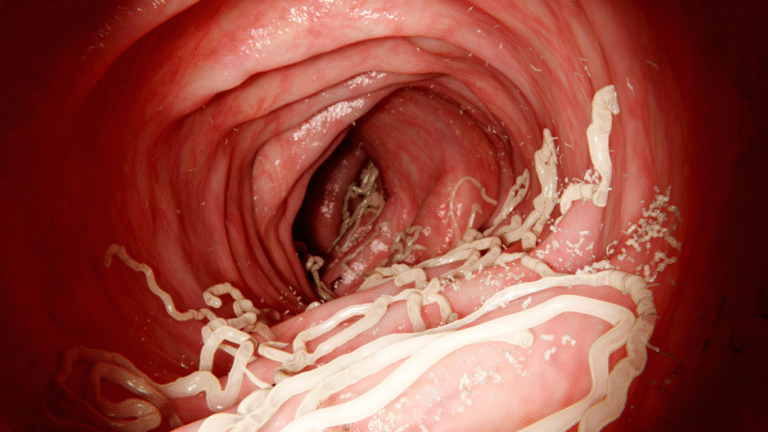

I wake up in darkness. I am an Ascaris roundworm, long and slim like a spaghetti noodle, about six to fourteen inches in length when fully grown. My world is cozy but tight–a warm tunnel deep inside a human’s small intestine. Around me, undigested food particles float like drifting clouds. Life inside this worm-filled tunnel feels steady, but the world outside is changing quickly.

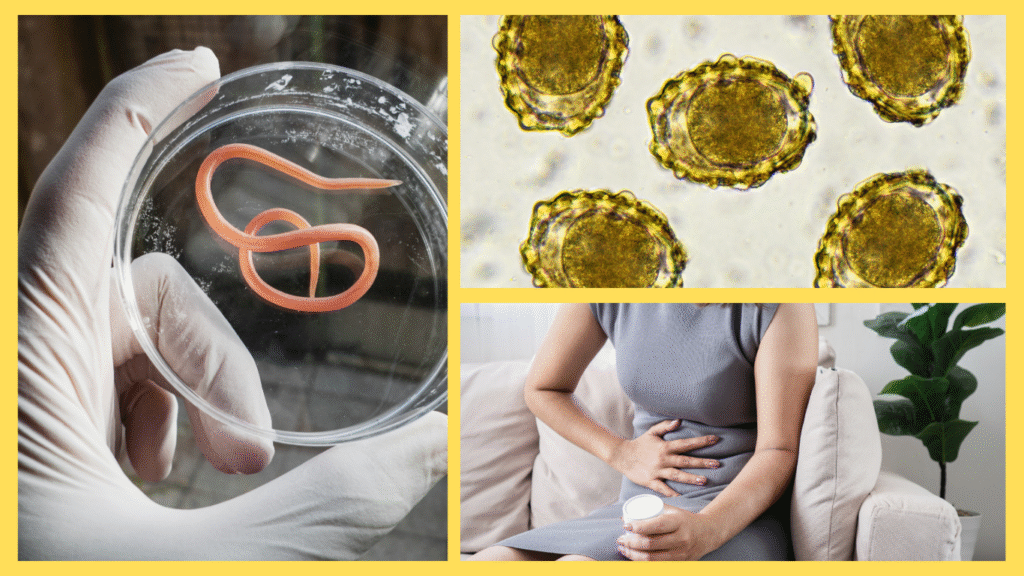

My day began long ago, surrounded by microscopic eggs that were passed through feces into the soil. Concrete turns to dirt, and soon those eggs enter a playground of warm soil–just the right temperature for me–where I stay dormant until a child unknowingly eats contaminated food or puts their hand in their mouth. That’s when everything changes for me. Humans often don’t wash their hands well, and from soil or poorly washed vegetables, I slip inside again (CDC source on transmission).

Once inside a human, I hatch. First, I become a tiny larva that penetrates the lining of the intestine and drifts into the bloodstream. I hitch a ride to the lungs, where I break free and wiggle until I reach the throat. Then I am swallowed back into the digestive system, this time returning to the intestine—my true home. This migration may cause children to cough or wheeze, often mistaken for asthma (NIH on life cycle).

When I settle back, I grow stronger. Nutrients in the gut feed me, and I molt until I become the full-grown Ascaris roundworm. Now I can be as long as a ruler and thick like a pencil. My body is smooth, with tapered ends, and I move by wriggling side to side. I share this crowded space with other members of my species, and together we disrupt digestion, cause discomfort, and sometimes block intestines–especially in children.

However, I am not invisible. Infected humans may feel belly pain, go through nasty bouts of diarrhea or constipation, and lose weight despite eating well. In more severe cases, families notice worms in vomit or stool–a jarring sight for any parent to see emerging from a child’s body. The Mayo Clinic explains that this colorful evidence often leads to diagnosis (Mayo Clinic on symptoms).

Meanwhile, the body fights back. Immune cells detect us in the gut lining and release signals that trigger inflammation. The intestine may swell, and symptoms like fever, nausea, or restlessness may follow–especially when multiple worms compete for space and food. Often, though, infections are mild and go unnoticed until complications arise.

Doctors treat me with medications like albendazole or mebendazole, strong drugs that kill me and allow the body to flush my remains out. One dose usually does the trick. Still, without treatment, I can live for months inside the host, laying thousands of eggs every day—eggs that will restart the cycle when they hit the soil. That’s why the World Health Organization organizes mass deworming in communities where I’m common (WHO on treatment and prevention).

By evening, I fade. Pills delivered through medicine courses into the body destroy me. The worms that remain are expelled. The human host redisovls digestive peace again, and I exist once more only as an egg in soil–waiting for the next human host.

My journey is simple yet powerful: soil to mouth, larva to lung, back to gut, to maturity, to eggs, and back into soil. For those living in areas without proper sanitation, I’m a frequent, unwelcome guest. But with clean water, improved toilets, good hygiene, and community treatments, my presence can be greatly reduced.

So when you brush your hands or ask for deworming at school, you’re protecting yourself from me. For an Ascaris roundworm, it’s just one more day battling to survive–but for humans, it’s a step toward a healthier life.

Sources

- CDC – Ascaris transmission and symptoms: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/ascariasis/

- NIH – Ascaris life cycle details: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513323/

- Mayo Clinic – Ascaris symptoms: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ascariasis/symptoms-causes/syc-20369086

- WHO – Treatment and prevention strategies: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections