Discover how Streptococcus mutans, the bacteria responsible for tooth decay, thrives in the mouth, causes cavities, and why some people never develop it at all.

The morning begins with sweetness. I am Streptococcus mutans, a tiny bacterium living in the soft, sticky film called dental plaque that coats the surface of human teeth. Around me are sugars left behind from a late-night snack: candy crumbs, juice, maybe even soda. To me, this is paradise. Sugar is my favorite food, and when I feast, I turn it into acid.

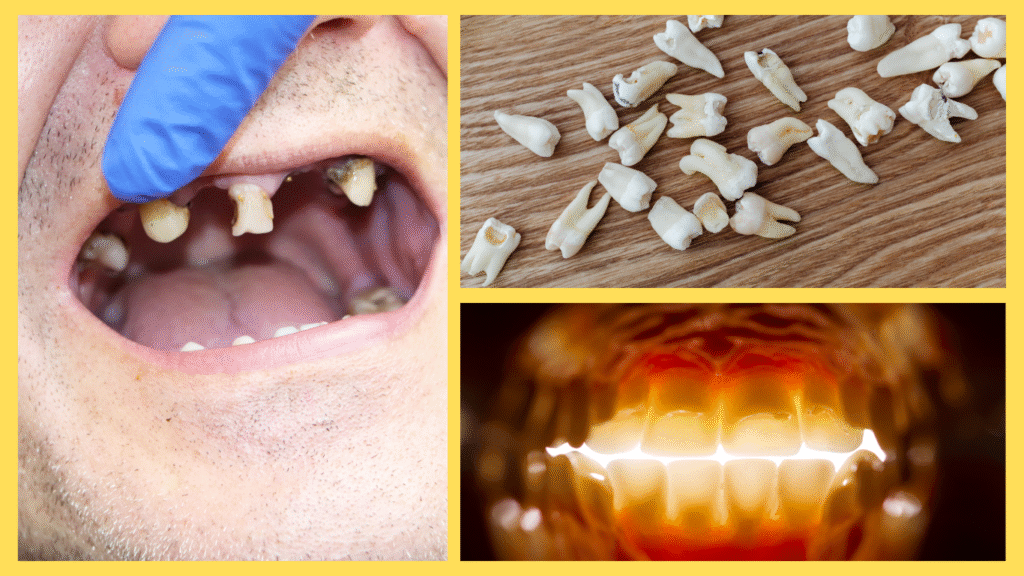

That acid doesn’t hurt me, but it slowly eats away at the tooth beneath me. Bit by bit, the enamel weakens, creating the perfect hiding place for me and my colony. For the human, this process feels like nothing at first. But over time, the small hole we carve turns into what dentists call a cavity (CDC).

However, my life wasn’t always here. I arrived in this mouth through something as simple as a kiss from a parent or sharing a spoon. Unlike some bacteria that are present at birth, I had to be passed from one person to another. Once I found my new home, though, I settled in for good. That’s why people who never pick me up—yes, they exist—may live their whole lives without ever having a single cavity. Without me, tooth decay doesn’t stand a chance (NIH).

Life in the mouth is never quiet. Saliva rushes around, washing away food particles and trying to keep the environment balanced. But when there’s too much sugar and not enough brushing, I thrive. I form thick biofilms—plaque—that even saliva struggles to break down. Inside this sticky shield, I multiply quickly, protected from most defenses.

Still, the human body doesn’t give up easily. Minerals in saliva, like calcium and phosphate, work constantly to repair the enamel I damage. Fluoride, from toothpaste or water, strengthens the teeth further, making them harder for me to attack. And of course, toothbrush bristles are my greatest enemy. Each stroke scrapes away my hiding places and exposes me to air and saliva, slowing down my progress (Mayo Clinic).

Meanwhile, dentists bring reinforcements. When the human visits, professionals remove plaque with tools I cannot escape. If I have already created a cavity, they fill the hole with materials that block me from returning. Fluoride treatments, sealants, and even simple advice about limiting sugar all work against me.

Yet despite the resistance, I remain one of the most common bacteria in mouths worldwide. I survive because humans often forget to brush, snack late at night, or sip on sugary drinks throughout the day. Every bite of candy or soda gives me another opportunity to grow. Consequently, millions of cavities are formed every year because of my persistence.

Still, I must admit, not every mouth welcomes me. Some humans truly never meet me, often because of family habits, hygiene, or luck. In these people, the absence of Streptococcus mutans means teeth remain cavity-free, even if they eat sugar. On the other hand, those who host me must stay vigilant.

As the day ends, I continue my work silently. My acids chip away at enamel, my biofilms strengthen, and my colony expands. But tomorrow might bring change. A determined brushing, a dentist’s drill, or even just a healthy diet could slow me down or stop me altogether.

For humans, the lesson is clear: I am small, but I am powerful. Cavities aren’t just about candy—they’re about me. By brushing twice a day, flossing, visiting the dentist, and limiting sugar, anyone can weaken my hold and protect their teeth.

I am Streptococcus mutans, the bacteria behind tooth decay. But in a world where dental care is consistent and awareness is strong, my story can end before it even begins.

✅ Key Sources for Facts