Discover how Pseudomonas thrives in hospitals, why it carries a strange grape-like odor, and how this deadly microbe resists antibiotics while endangering vulnerable patients.

The day begins in a damp corner of a hospital sink, where I, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, quietly multiply. To the human eye, I am invisible. But if you could lean in close enough, you might notice something peculiar — the faint scent of grapes. That sweet smell is my calling card, produced by chemicals I release as I grow. Some doctors recognize me instantly by it. They know that when grapes drift through the air in a place they don’t belong, danger has arrived.

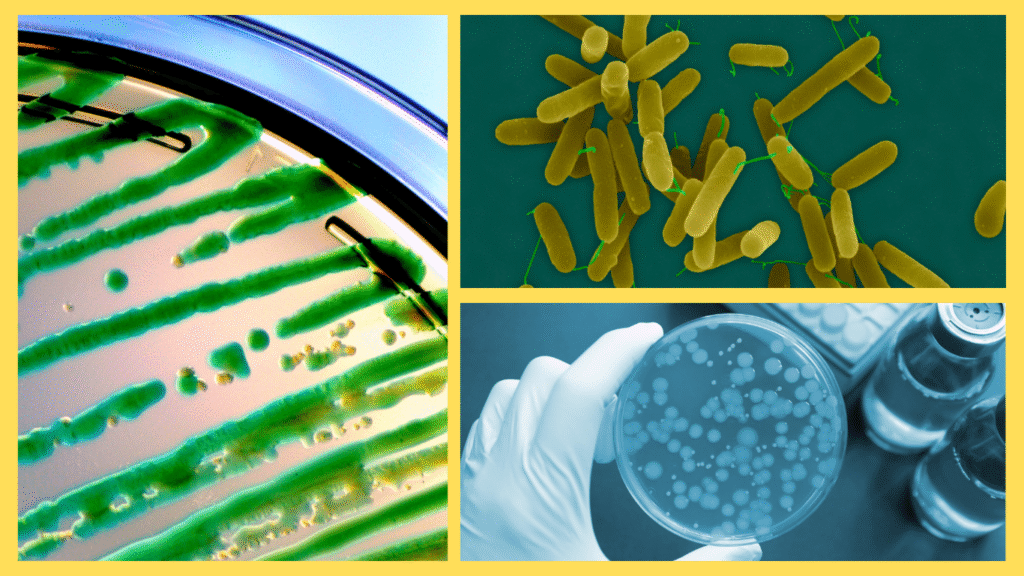

For me, life here is perfect. I thrive in moist places — sinks, catheters, ventilators, even soap dispensers. While most bacteria need special conditions, I am remarkably adaptable. I can grow in water, on plastic, or inside the human body. I feast on whatever nutrients are available, and I am shielded by my biofilm, a slimy coat that makes me especially hard to kill. In the hospital, surrounded by vulnerable patients, I couldn’t ask for a better home.

My favorite targets are people whose defenses are already weak. A healthy human might barely notice me, but someone with a weakened immune system is another story. Burn patients, cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, or those hooked up to ventilators provide me with the perfect opportunity. I slip into wounds, invade lungs, or ride catheters into the bloodstream. Once inside, I set to work multiplying, leaving behind that grape-like odor as a warning sign no one should ignore (CDC).

The moment I enter the human body, the battle begins. White blood cells rush to stop me, trying to engulf and destroy my colonies. However, I am clever. I release toxins that damage tissues and disable immune cells. My arsenal includes enzymes that break down barriers and pigments like pyocyanin, which give infected wounds a greenish-blue color. These tools make me more than just a nuisance — they make me deadly. Pneumonia, bloodstream infections, urinary tract infections, and wound infections are all part of my repertoire. For people who are already sick, my arrival can turn survival into a steep uphill climb (Mayo Clinic).

But what makes me truly dangerous is not just my ability to infect. It is my resistance. While other microbes may fall quickly to antibiotics, I resist many of them with ease. I have pumps that spit out the drugs before they can harm me. I can even swap pieces of genetic material with other bacteria, learning new tricks for survival. This adaptability allows me to outwit treatments and linger inside patients for weeks or months. Infections caused by me are among the hardest for doctors to treat. In fact, some strains of mine are resistant to nearly all available antibiotics, making me a nightmare in intensive care units (NIH).

Inside a patient’s lungs, the battle is intense. For someone with cystic fibrosis, thick mucus in the airways provides me with the perfect hiding place. I build my biofilm there, forming a slimy fortress that shields me from both immune cells and antibiotics. As a result, I become a chronic infection, flaring up again and again. Each cough from the patient carries my scent — faint grapes with a touch of rot. It’s a cruel reminder that I am still there, still thriving.

Meanwhile, doctors scramble. They test antibiotics, trying one drug after another, hoping to find something I haven’t resisted. Sometimes they combine two or three drugs, overwhelming me from multiple angles. Other times, they must resort to last-resort medications that can have harsh side effects. For the patient, treatment is grueling. For me, it’s simply another challenge in my daily survival.

Yet, I am not unstoppable. Infection control measures make my life much harder. When healthcare workers wash their hands, sterilize equipment, and isolate infected patients, I lose opportunities to spread. Chlorine disinfectants and proper sterilization can wipe me out on surfaces. And in patients, new research into phage therapy — using viruses that attack bacteria — may one day become another weapon against me. While I’ve learned to resist many antibiotics, I haven’t figured out how to resist everything. For now, humans still have a fighting chance.

Still, I can’t deny the irony of my existence. To me, that grape scent is just a chemical byproduct, nothing more. But to humans, it’s a sign of danger wrapped in sweetness — like a poisoned gift. Doctors say that when they smell grapes in the hospital and no fruit bowl is in sight, they know I’m near. My smell is a warning, but one that comes too late for some.

My day, like so many others, ends in uncertainty. In one patient, I survive, resisting treatments and spreading further. In another, doctors catch me early, wiping me out before I can do harm. My survival depends on chance, opportunity, and human error. All I know is that as long as there are damp corners, weak immune systems, and lapses in sanitation, I will always find a way to return.

The lesson, however, is not mine but yours. I am Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the deadly microbe with the grape-like scent. I flourish where hygiene fails, where treatments falter, and where vigilance slips. Humans may never eliminate me completely, but they can keep me in check. Handwashing, careful hospital practices, and appropriate antibiotic use are not just precautions — they are the difference between my quiet survival and a patient’s life.

So the next time someone mentions the smell of grapes in a hospital, don’t imagine sweetness. Imagine me, lurking in the shadows, waiting for my chance. And remember: while I am clever, deadly, and persistent, knowledge and care are my greatest enemies. Humans who take the time to protect themselves and others can end my story before it ever begins.