Discover how Giardia, the tiny parasite behind severe diarrhea, lives and spreads. Learn how to protect yourself and your pets from this common infection.

The morning begins with a shimmer across a cold mountain stream, where the water dances over rocks and catches the light like scattered diamonds. To hikers and their dogs splashing playfully nearby, the stream looks pure and inviting, but hidden within the current, I drift unnoticed. I am Giardia lamblia, a microscopic parasite responsible for giardiasis, and though invisible to the naked eye, I am very real. Wrapped in a protective cyst, I wait patiently for the next sip of water, a lick from a thirsty dog, or a careless gulp from a human hiker. Life in the stream is calm, yet I know my world will change the moment I am swallowed.

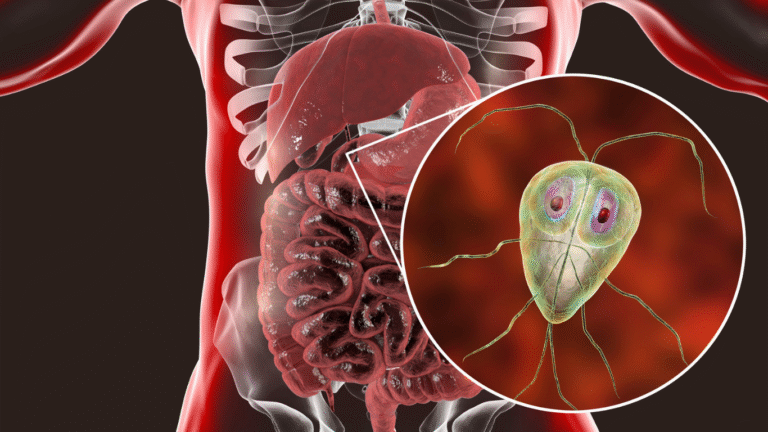

Before long, a Labrador bounds down the trail, tongue lapping eagerly at the cool stream. In that instant, I seize my chance. Carried inside the water, I slip past his mouth, glide down the esophagus, and enter the stomach. The acid here is harsh, meant to destroy invaders, but my tough outer shell keeps me safe. This cyst is my armor, my survival tool, allowing me to endure the stomach’s hostility until I reach the small intestine. Once there, I shed my shell and transform into my active form, a flagellated organism with tiny whip-like tails that propel me forward. The small intestine is warm, moist, and rich in nutrients—a perfect home for me to thrive.

At first, the dog feels nothing. He races through the meadow, tail wagging, oblivious to my presence. But as I divide again and again, multiplying into thousands, I begin to cover the lining of his intestines. I do not pierce the tissue, but I cling tightly, creating a carpet of parasites that interferes with his ability to absorb nutrients and water CDC. What was once a happy stomach begins to feel unsettled. Soon, watery diarrhea follows, sometimes sudden and explosive. The dog grows gassy and bloated, his once eager appetite fading. Instead of bounding with joy, he lies down more often, looking tired and thin. For some dogs, the illness lingers only a few weeks, but for others, especially the young, old, or weak, giardiasis can last for months if left untreated Mayo Clinic.

Meanwhile, the dog’s immune system notices something is wrong. White blood cells surge to the intestines, trying to capture and destroy me. In certain cases, this defense is strong enough to push me out on its own, flushing me away with diarrhea. But often, I am stubborn, holding fast to the gut lining. This is when veterinarians must step in. When the dog’s family notices his sudden weight loss, soft stool, or the greasy, foul smell of his diarrhea, they rush him to the clinic. There, a stool test reveals my presence, and treatment begins. Medicines like fenbendazole or metronidazole are prescribed, designed to target and kill me NIH. As the drugs spread through the intestine, my flagella slow, my numbers shrink, and my grip on the host weakens until I am forced out.

While dogs are my most common victims, I do not ignore humans. When hikers drink untreated water from rivers or streams, I find my way into their bodies as well. The symptoms I cause are strikingly similar—diarrhea, stomach cramps, nausea, fatigue, and weight loss. In people, I sometimes leave no symptoms at all, but in others, I create weeks of discomfort that disrupt daily life CDC. For both dogs and humans, dehydration becomes a real concern, especially when diarrhea is severe and persistent. And because I spread through stool, poor sanitation or skipped handwashing gives me the perfect opportunity to leap from one host to the next.

Even as treatment works against me, my cycle continues. Some of my cysts leave the body through feces, often into soil, water, or shared environments. If waste is not properly disposed of, I may survive for weeks outside a host, still infectious and waiting. When a dog at the park sniffs or licks contaminated grass, or when rain carries runoff into streams and puddles, I find new opportunities. Even a single mouthful of contaminated water can be enough to restart my story in a new body CDC.

Because I am so resilient, prevention becomes the strongest defense against me. For dogs, this means avoiding stagnant water, practicing regular hygiene, and seeking veterinary care quickly when symptoms appear. For humans, prevention requires extra care while camping, hiking, or traveling. Water that looks clear can still be filled with my cysts, so boiling or filtering before drinking is critical. Handwashing after using the bathroom, cleaning up after pets, and avoiding contaminated food are simple but powerful tools against me. When these habits are followed, my cycle breaks, and I lose my chance to spread.

Eventually, in the Labrador’s case, the medicine finishes its work. My once-thriving colony collapses, flushed away with waste, leaving behind a recovering intestine. The dog regains his energy, his stool firms up, and his appetite returns. His family is relieved, though they remain more cautious now when letting him drink from streams or ponds. My presence has left a lesson, one that lingers long after I am gone.

And so my day ends where it began, not in triumph but in retreat. I remind both humans and dogs that nature, while beautiful, carries hidden dangers. A sparkling stream may hold a parasite, a playful puddle may conceal a threat, and the smallest oversight in hygiene may open the door to illness. Yet I am not invincible. With vigilance, clean water, careful sanitation, and timely treatment, I can be prevented and defeated.

After all, I am only a parasite searching for a home. But with awareness and care, dogs and humans alike can keep me from ever moving in.

Sources: