Discover the story of Penicillium, the humble mold that gave rise to penicillin and transformed modern medicine. Learn how it works, its history, and its lasting impact.

It is damp and cool inside the forgotten corner of a loaf of bread. Threads of green and blue mold spread silently, weaving across the surface like tiny forests on a miniature landscape. Life for me, Penicillium, is simple. I feed on the carbohydrates around me, breaking them down to grow stronger and extend my reach. I am one of the oldest inhabitants of Earth’s ecosystem. You can find me in soil, on decaying fruit, or even drifting unseen in the air. For centuries, humans thought of me as a nuisance — the fuzzy growth that spoiled food. However, what they didn’t know was that hidden inside my cells was a secret that would eventually change the future of medicine forever.

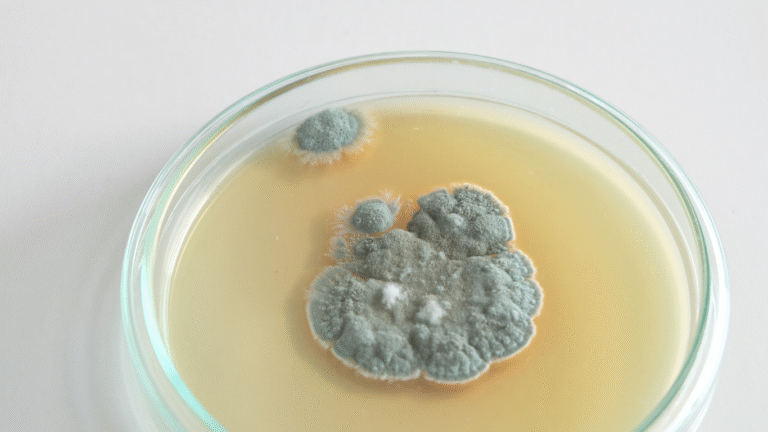

My quiet life of feeding and growing could have gone unnoticed. But then came 1928, a fateful year when a scientist named Alexander Fleming left his Petri dishes of Staphylococcus aureus — a dangerous bacterium — uncovered on his workbench. While he was away, I drifted in from the environment and landed softly on one of his dishes. As I spread my delicate filaments across the surface, something remarkable happened. Around me, the bacteria began to disappear. A clear circle formed where no bacteria could survive. Fleming was puzzled, but soon he realized my secret: I produce a powerful chemical that kills or stops bacteria from multiplying. He named this substance penicillin, after me, Penicillium notatum.

For me, it was simply a way to defend my territory. I did not like to share my food with aggressive bacteria, so I evolved to make penicillin as a weapon. But for humans, it was nothing short of miraculous. At that moment, an ordinary mold had revealed the world’s first true antibiotic.

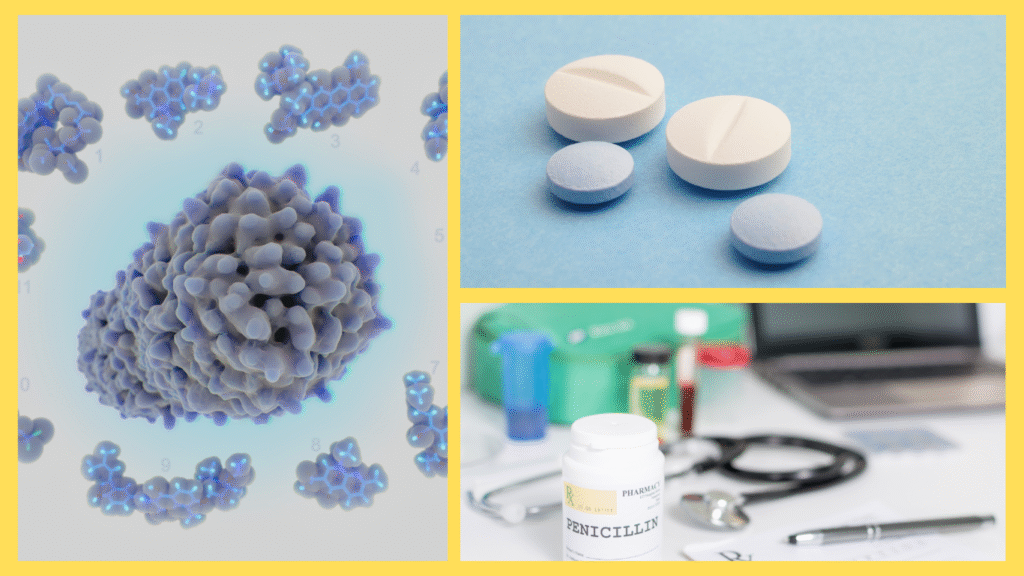

The way penicillin works is both simple and ingenious. Bacteria, unlike humans, rely on strong protective walls around their cells. These walls keep them from bursting in watery environments. My penicillin sneaks in and blocks the construction of those walls, leaving the bacteria weak and vulnerable until they collapse and die (CDC). Therefore, what began as my personal defense mechanism became the foundation of one of the most important discoveries in medical history.

Still, Fleming’s discovery was only the beginning. Humans knew about me, but they did not yet know how to harness me effectively. Producing penicillin in large amounts proved incredibly difficult. My moldy colonies were delicate, and the quantities of penicillin I produced seemed impossibly small. Yet scientists refused to give up. In the early 1940s, a group led by Howard Florey and Ernst Chain worked tirelessly to develop methods to grow me in massive fermentation tanks. They even searched through different strains of Penicillium to find those that could make more penicillin. Slowly, their efforts paid off.

The timing could not have been more urgent. World War II was at its peak, and soldiers were dying not only from bullets but from infections in their wounds. For centuries, even a small cut could turn deadly when bacteria invaded. Suddenly, with penicillin available, doctors could treat those infections and save lives. Reports from the battlefield described miraculous recoveries. By the end of the war, penicillin was being called the “wonder drug,” and my once-overlooked mold body had become a global hero (NIH).

The impact spread quickly. Before penicillin, illnesses such as pneumonia, scarlet fever, and syphilis often meant slow decline or death. Hospitals were full of patients suffering from infections doctors could do nothing about. After penicillin, survival rates soared. For the first time, humans had a weapon powerful enough to defeat bacteria that had plagued them for centuries. As a result, medicine entered a new era. Surgeries that were once too risky because of infection became safer. Childbirth, which had carried high risks for mothers and newborns, became much less deadly. Even organ transplants eventually became possible because antibiotics could control infections that would have otherwise been fatal (Mayo Clinic).

Of course, not all of my relatives became famous for medicine. Some of my cousins in the Penicillium family earned recognition in kitchens instead of hospitals. Humans discovered that we could transform ordinary milk into cheeses like Roquefort, Camembert, and Brie. Our unique flavors and textures delighted generations of food lovers. Others among us, however, developed darker reputations. Certain species spoil food, while others can even produce harmful toxins. Yet, in the balance of things, my contribution through penicillin stands as one of the greatest gifts nature has ever given humanity.

However, the story did not remain one of triumph alone. Over time, bacteria proved themselves to be clever survivors. They began to adapt, finding ways to resist the effects of penicillin. Some produced enzymes capable of breaking down the drug before it could harm them. Others changed their cell walls so the drug could no longer bind effectively. This process, known as antibiotic resistance, is now one of the greatest threats to global health (CDC). Infections that were once easily cured with penicillin have become more stubborn, forcing doctors to turn to stronger and sometimes more toxic antibiotics.

Consequently, humans now face a serious challenge. The miracle I provided is at risk of being lost if antibiotics are misused or overprescribed. Every unnecessary dose gives bacteria another chance to evolve and fight back. That is why experts today emphasize the importance of using antibiotics only when needed and always completing the prescribed course of treatment. The effectiveness of drugs like penicillin must be protected so that future generations can benefit from them just as much as those in the past.

As for me, I remain a humble mold, often overlooked in the corners of kitchens or drifting invisibly through the air. I did not choose fame, but I became a turning point in human history. My discovery reminds people that nature holds secrets waiting to be uncovered, sometimes in the most unexpected places. Even something as small and ordinary as mold can hold the key to saving millions of lives.

And so, as my day in the damp shadows continues, I think of the soldiers who walked away from infected wounds because of me, the children who survived pneumonia, and the countless patients who found hope in hospitals. My life may begin on forgotten bread, but my legacy reaches every corner of the modern world. The story of Penicillium is a reminder that sometimes the simplest organisms carry the greatest power — and that even in the fight against disease, the smallest allies can change the game forever.