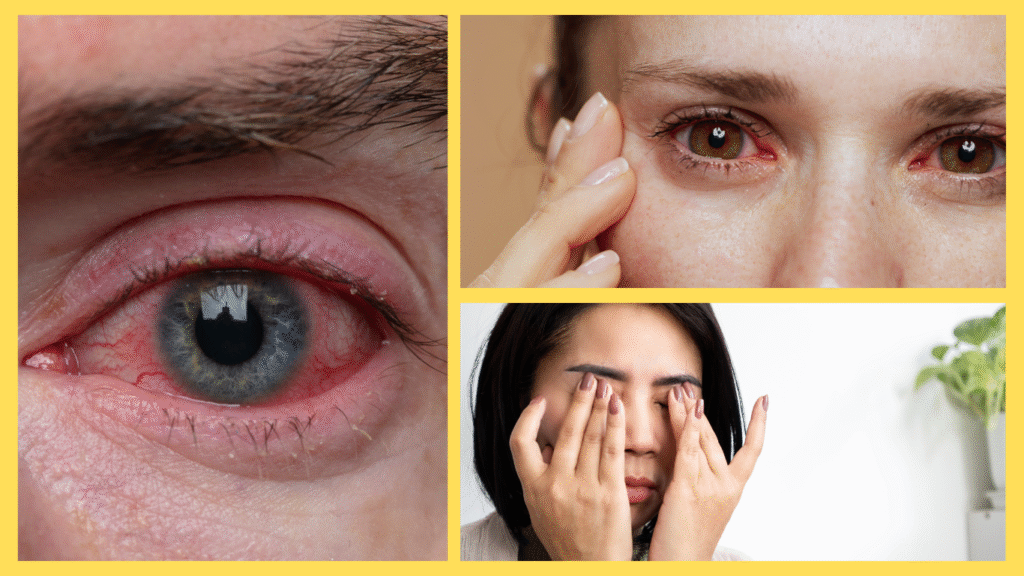

Ever wondered what causes red eyes? Step into the life of the microbes behind conjunctivitis and learn how they spread, infect, and how your body fights back.

The morning light filters softly through the thin surface of the human eye, though for me, a tiny adenovirus, it feels more like stepping into a vast ocean of saltwater. My world is warm and moist, a delicate balance of tears, proteins, and tiny defenses that usually keep intruders away. I drift quietly on this tear film, surrounded by other invisible creatures. Some are bacteria that simply live on the eyelashes or skin, minding their own business. Most of the time, the eye is a calm, protected environment. But my presence here is about to disrupt everything.

I did not arrive here on my own. Someone rubbed their eyes after shaking hands, or perhaps shared a towel with another person already battling irritation and swelling. That’s how I got carried into this new home. It’s a simple journey, really, one that happens more often than people realize. Humans call it “viral conjunctivitis,” but most just call it pink eye. To me, it is simply survival.

The eye is not an easy place to live. Tears wash across its surface constantly, filled with enzymes like lysozyme that can break down invading microbes. Blinking creates waves that sweep particles toward the edges, and a thin mucous layer helps trap outsiders before they get too comfortable. Still, even the strongest defenses have small cracks, and today I find mine. Maybe the eye was rubbed too hard, leaving the tissues irritated. Maybe dust or pollen already caused tiny inflammation. Whatever the reason, I slip past the surface and find myself face to face with the cells of the conjunctiva.

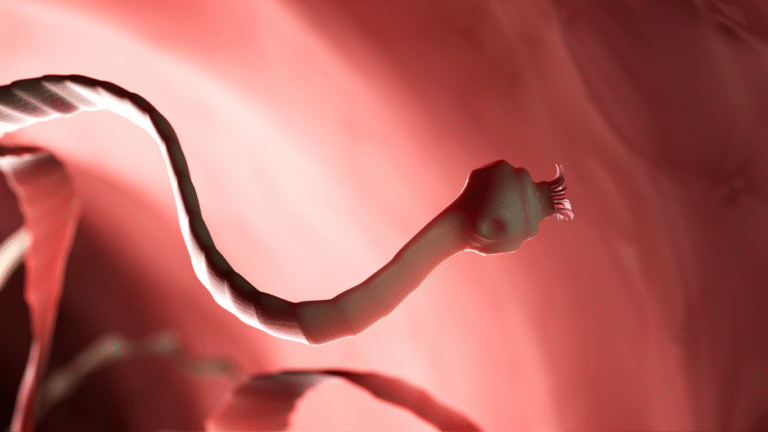

This is where my work begins. I am not alive in the same way a bacterium is. I cannot eat, grow, or move on my own. What I can do is hijack. I attach to the surface of a cell using my proteins, which fit into the cell’s receptors like a key in a lock. Once inside, I unwrap myself and pour my genetic instructions into the cell’s nucleus. Suddenly, the host cell is no longer working for the human—it is working for me. It makes copy after copy of my viral parts until it can no longer hold them all. Then the cell bursts, spilling out hundreds of my offspring into the surrounding tissue.

The human begins to notice the change almost immediately. The whites of the eyes grow red as blood vessels swell with immune cells rushing to the surface. The eyes water, not out of sadness but out of defense. Tears try to wash me away, while the person feels the constant urge to rub, which only spreads me further. To the human, it is an irritating, uncomfortable day. To me, it is victory.

I am not alone in this fight. Other microbes, bacterial cousins like Staphylococcus aureus or Haemophilus influenzae, sometimes take advantage of irritated eyes as well. They cause thicker, stickier discharge and may require antibiotics to treat. But antibiotics do not affect me. I am a virus, and medicine designed for bacteria passes right through me, useless. For the unlucky human, this means there is no quick cure. Relief comes only through patience, rest, and careful hygiene.

Still, my triumph is not guaranteed. The human body has faced me and my viral kind many times before. Soon, white blood cells arrive at the scene, patrolling the tissue like soldiers on alert. Some release chemical signals that cause swelling and heat, making the environment less comfortable for me. Others, called T cells, are more precise. They recognize patterns unique to my structure and begin destroying every cell I have infected. The redness and itchiness the human feels are not caused directly by me, but by this fierce battle taking place at a microscopic level.

Meanwhile, the human takes action too. Cold compresses are pressed against the eyelids, offering temporary relief. Hands are washed more often, and the person avoids sharing pillows, towels, or makeup to prevent me from spreading to friends and family. Even though I can survive for hours on surfaces like doorknobs or fabrics, these small acts of hygiene reduce my chances of finding a new host.

As hours turn into days, my numbers begin to dwindle. The immune system has learned my patterns and now attacks me more efficiently. Tears increase, flushing me out with every blink. Some of my viral offspring manage to slip onto hands or nearby objects, waiting for the chance to infect another person. But here, in this particular eye, my time is almost up.

By the fourth or fifth day, the human is already beginning to feel better. The swelling decreases, the redness fades, and the constant itch becomes only a memory. My once-thriving population has been reduced to nothing. For me, it is the end of my story. For the human, it is a return to normal life, though perhaps with a newfound respect for how quickly something as small as me can disrupt daily routines.

Yet, even as I fade, I know my kind will never disappear. Adenoviruses are common, spreading easily from person to person, especially in crowded places like schools, offices, and households. A single careless touch of the face, a quick rub of tired eyes, or a forgotten handwash can give me the chance to start the cycle all over again. This is why doctors and health experts always emphasize prevention. Good hygiene—regular handwashing, not sharing personal items, and avoiding unnecessary contact when infected—remains the strongest defense against me.

Occasionally, I think about my bacterial cousins. Unlike me, they can sometimes cause more serious complications if left untreated. That is why doctors sometimes prescribe antibiotic eye drops when bacteria are involved. But for me, medicine has little power. The immune system itself is my true opponent, and time is what allows the body to win. Humans often underestimate their natural defenses, but I know firsthand just how powerful they can be.

In the end, my life is short, chaotic, and often cut down by forces larger than myself. But in those brief days, I can cause watery eyes, sleepless nights, and an uncomfortable itch that humans never forget. They call it red eyes, pink eye, conjunctivitis—different names for the same battle. To me, it is simply survival, a day in the life of a microbe that thrives only when defenses slip.

So the next time a person wakes up with sticky eyelids, blurred vision, and bloodshot whites, they should remember that it might just be one of us living out our fleeting story. With good habits and patience, the human always wins in the end. But until then, I will continue to drift, waiting for the next opportunity, the next careless touch, the next tired rub of the eye that lets me in.

Sources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Conjunctivitis (Pink Eye)

- Mayo Clinic – Pink Eye (Conjunctivitis)

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) – Viral Conjunctivitis