Follow the journey of Lyme disease bacteria- from tick habitat to human infection- in a simple and engaging narrative that blends science, transitions, and useful health tips.

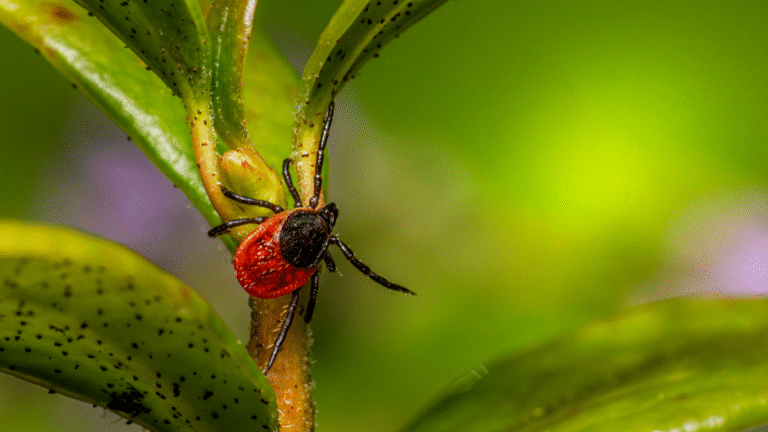

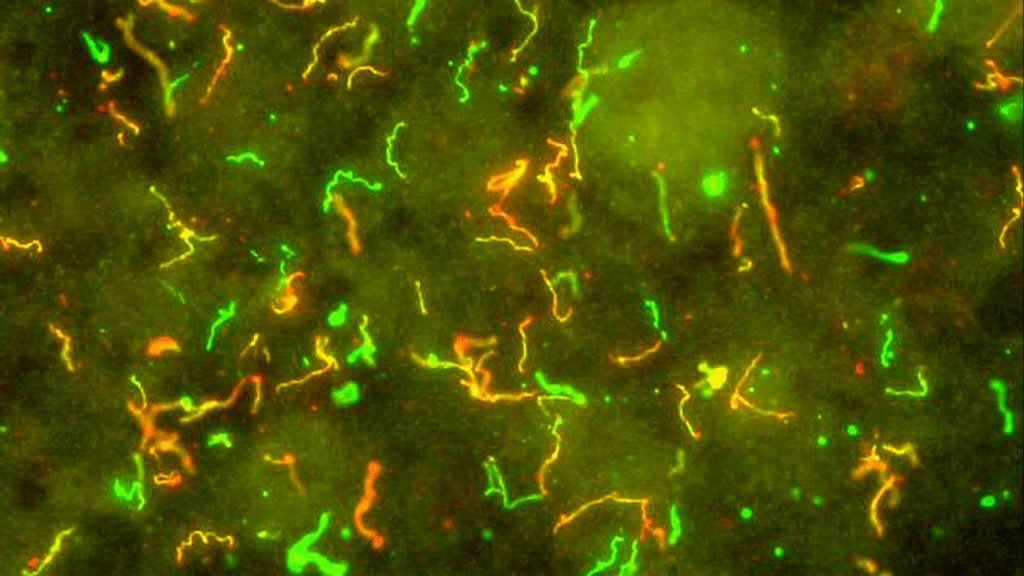

The morning dew still clings to a blade of grass as I wake in the quiet world underfoot. I am Borrelia burgdorferi, the spiral-shaped bacterium responsible for Lyme disease, stretching my corkscrew body in the damp shade where ticks roam close by. My home is cool, moist, and shadowed by fallen leaves. Above me, the blacklegged deer tick, Ixodes scapularis– waits patiently, front legs outstretched in a posture called “questing,” ready to latch onto any passing animal. Life is calm, almost still. Yet, I know change is near.

Before long, a nymph tick brushes against me. Its body is smaller than a sesame seed, but to me, it feels like a vast vessel of opportunity. Without hesitation, I climb aboard, curling into the tick’s midgut where I settle in. The tick doesn’t notice me; it simply carries me forward in its life cycle. When it finds its next meal, a mouse, a deer, or sometimes even a bird, I multiply quickly, readying myself for a larger journey. Eventually, when the tick feeds again, I make my move, migrating to its salivary glands so I can enter the bloodstream of a new host (CDC – Transmission).

The moment finally arrives when the tick bites into human skin. Perhaps it’s a hiker exploring tall grasses or a child playing in the woods. The bite is silent, painless, unnoticed. Through the tick’s saliva, I slip beneath the skin, and my story within the human body begins. This moment feels electric, a transition from hidden dormancy to active invasion.

Once inside, I twist and spin through the layers of skin, swimming with my spiral motion. As I move outward, I leave behind a mark of my presence: a rash called erythema migrans. To the human eye, it looks like a spreading circle, sometimes shaped like a bull’s-eye. Over days, the redness expands, warm to the touch and often tender (Mayo Clinic). Alongside this, the host begins to feel tired, achy, and feverish. Headaches press behind the eyes, joints ache like after a hard day of labor, and chills set in. To them, it feels like the flu. To me, it is success—evidence that I am no longer confined to the skin.

Meanwhile, I push further, slipping into the bloodstream. The current pulls me forward, carrying me to joints, heart tissue, and even nerves. This is where I show my true reach. In some hosts, I stir swelling in the knees that makes even walking painful. In others, I disrupt signals in the face, leading to paralysis known as Bell’s palsy. On rare occasions, I inflame the protective tissue around the brain and spinal cord, leading to Lyme meningitis. The body tries to fight back, sending white blood cells to destroy me. Yet, my corkscrew shape allows me to move between tissues and hide, evading their grasp.

Doctors know my patterns well now. When a patient shows up with a bull’s-eye rash or a combination of fever and fatigue after being outdoors, they often recognize Lyme disease quickly. The usual treatment is a course of antibiotics-doxycycline for most adults, or amoxicillin or cefuroxime for younger children and pregnant women. If given early, these medications are remarkably effective, clearing me out of the body within weeks. For the human, recovery feels like a weight lifting, the fever breaks, the fatigue fades, the joints loosen again.

However, when treatment is delayed, my impact grows heavier. If weeks pass without antibiotics, I may spread further, causing Lyme arthritis with swollen, painful joints, or heart complications like an irregular heartbeat known as Lyme carditis. In some cases, nerve pain or tingling sensations appear, unsettling reminders of how far I’ve traveled. Though most people recover, some continue to feel exhausted, foggy, or sore even after antibiotics. Doctors call this Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome, and while extended antibiotic use doesn’t help, patients benefit from supportive care and monitoring.

While my presence in one body may be short, I rely on the tick to continue my story. After finishing a blood meal, the tick may drop into the leaf litter, molting and waiting for another host. Deer, mice, chipmunks, and even domestic animals like dogs and cats may carry both ticks and me. In this way, the cycle between wildlife, ticks, and humans continues season after season, especially in wooded or grassy regions of North America, Europe, and Asia where Lyme disease is most common.

For humans, prevention becomes the sharpest weapon against me. Avoiding tick habitats is one step, but when the woods call, they can still protect themselves. Wearing light-colored clothing makes ticks easier to spot. Tucking pants into socks and using insect repellents with DEET or picaridin create barriers against the tick’s bite. Treating clothes with permethrin gives another layer of defense. And perhaps most importantly, checking the body carefully after spending time outdoors can stop me before I ever take hold. A tick removed within 36 hours rarely has time to transmit me. Even pets need protection, since ticks can hitch rides indoors on their fur (CDC – Protecting Pets).

Imagine the difference these steps make. A family hikes the same trail in summer: one wears shorts and never checks for ticks afterward, while another wears long pants, applies repellent, and checks carefully before heading home. For the first, I may become an uninvited guest. For the second, I remain stranded in the forest, unable to begin my story. Prevention, as simple as it seems, changes the outcome dramatically.

As night falls in the human body, my own day reaches its turning point. For some hosts, antibiotics and the immune system are already closing in, and my numbers dwindle. For others, if left untreated, I settle deeper, making myself harder to dislodge. Yet, I am not invincible. Time and vigilance work against me, and science has taught humans how to recognize, diagnose, and treat Lyme disease effectively.

In the end, my story is less about me and more about the balance between humans and the hidden world they walk through. The forest floor, the deer that wander at dusk, the tiny nymph tick on a blade of grass—all are connected. I am only one thread in that web, small but significant. For humans, the lesson is clear: prevention is easier than cure. Protect yourself in tick country, check your skin after outdoor adventures, and act quickly if a rash or fever appears. Lyme disease does not have to define anyone’s life.

And so, as I fade from this host, either defeated by antibiotics or stopped by prevention, I leave behind only a reminder. Even the tiniest creatures, unseen to the eye, can ripple through a person’s days. But with awareness, care, and science on their side, humans can keep my story short, and keep their own lives moving freely, unbent by the weight of disease.