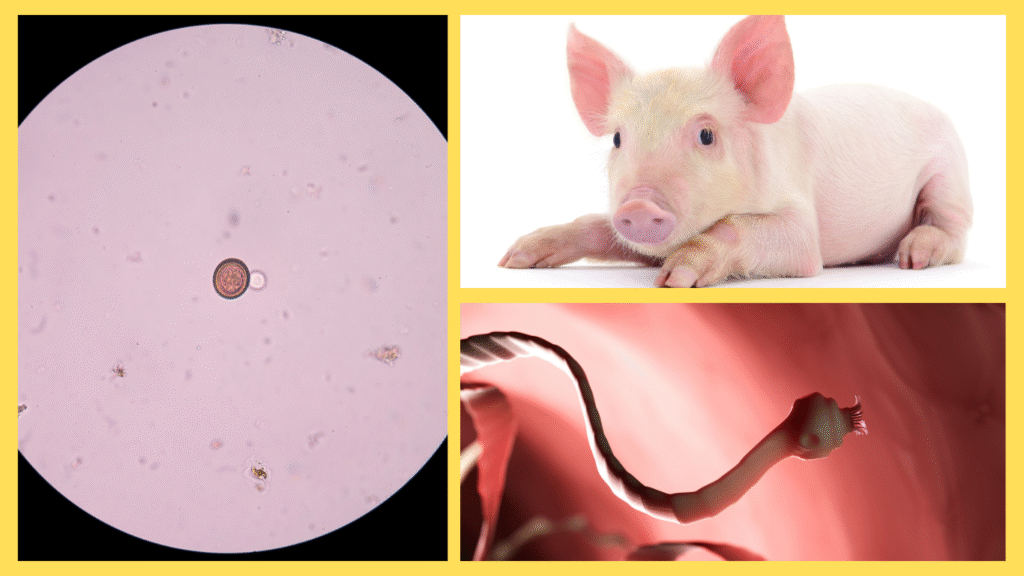

Discover how Taenia solium infects pigs, bears, and eventually humans due to neglect, and why proper food safety remains key to preventing tapeworm infections.

The day begins inside a quiet pile of feces left in the forest. I am an egg of Taenia solium, better known as the pork tapeworm. My shell protects me from sun and rain, waiting for the moment when an unsuspecting creature comes along. Out here, wildlife is my playground. Pigs root in the soil, bears forage in the underbrush, and sooner or later, one of them swallows me whole without even realizing it.

For me, this is the start of an adventure. Once inside a pig’s stomach, my shell dissolves, and I burst free. I latch onto the gut wall, burrowing into tissues and making myself at home. Over time, I transform into tiny larvae, drifting into muscles where I curl into cysts. In pigs, I stay quiet and patient, waiting for the day a human takes a careless bite of undercooked pork.

Bears, though, offer a wilder ride. Their diets are unpredictable, and sometimes they swallow infected meat. In their massive muscles, I settle in just the same. But unlike pigs, bears are often hunted — and here lies my chance. When hunters skin their prey, slice into the meat, and roast it just enough to taste wild, I sometimes survive the heat. As a result, I find myself inside humans.

Humans are supposed to know better. Cooking meat thoroughly kills me. Washing hands after handling animals removes my eggs. Yet neglect remains my greatest ally. In many places, sanitation is weak, and meat inspection is limited. Pigs roam freely, eating whatever they find. Hunters carve up their game without much thought. And when people eat raw or undercooked meat, I thrive [CDC].

Inside humans, my life changes dramatically. If my host swallows my cysts in pork, I grow into a long adult tapeworm inside their intestines. There, I can stretch several meters, quietly feeding on nutrients and releasing eggs into their stool. The cycle begins again. However, if my eggs are swallowed directly — often because of poor hygiene — the results are far worse. My larvae can migrate to muscles, eyes, and even the brain, causing a disease called cysticercosis. When the brain is involved, it’s called neurocysticercosis, a leading cause of seizures in many parts of the world [Mayo Clinic].

From my perspective, it’s just survival. But for humans, the consequences are devastating. Seizures, headaches, and neurological damage are no small price to pay for neglecting basic safety. Consequently, public health experts constantly remind people to cook pork and wild game to safe temperatures, wash hands, and keep pigs penned away from human waste [NIH].

Still, my story isn’t without a little humor. Consider hunters who proudly display their game, imagining themselves invincible conquerors of the wild. Even Robert F. Kennedy Jr., famous for his love of hunting, might chuckle at the thought that a microscopic worm like me could set up camp in his head. After all, nothing humbles a tough outdoorsman quite like realizing his prized trophy dinner might come with a side of tapeworms.

Yet, humor aside, the truth is clear: humans often underestimate microbes like me. I am invisible but efficient. I cross the boundaries between wildlife and humans with ease, thanks to neglect in cooking, sanitation, and care. For pigs and bears, I am just a hitchhiker. For humans, I can be a lifelong burden.

The turning point in my story comes when medicine intervenes. Drugs like praziquantel can kill me, breaking my hold on the intestine. In cases of cysticercosis, more complex treatments are needed, including anti-inflammatory medications to manage swelling as my larvae die off [CDC]. Therefore, while I am dangerous, I am not unbeatable. Humans have the tools to stop me — if only they use them.

My day ends not with triumph but with reflection. For centuries, I have moved through pigs, bears, and humans, thriving on neglect and carelessness. I have survived campfires, kitchens, and even medicines. But I cannot outsmart knowledge. Every time a human cooks pork thoroughly, inspects game meat, or improves sanitation, my chances dwindle.

Health message: Taenia solium infections are entirely preventable. By practicing good hygiene and food safety, humans can keep me from ever finding a home in their bodies. It may not be as thrilling as a wild hunt, but it’s far safer — and it keeps worms where they belong: in cautionary tales, not in your head.

Sources:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Taeniasis: About

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Treatment for Taeniasis

- Mayo Clinic. Taeniasis Symptoms & Causes

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Taenia solium and Cysticercosis