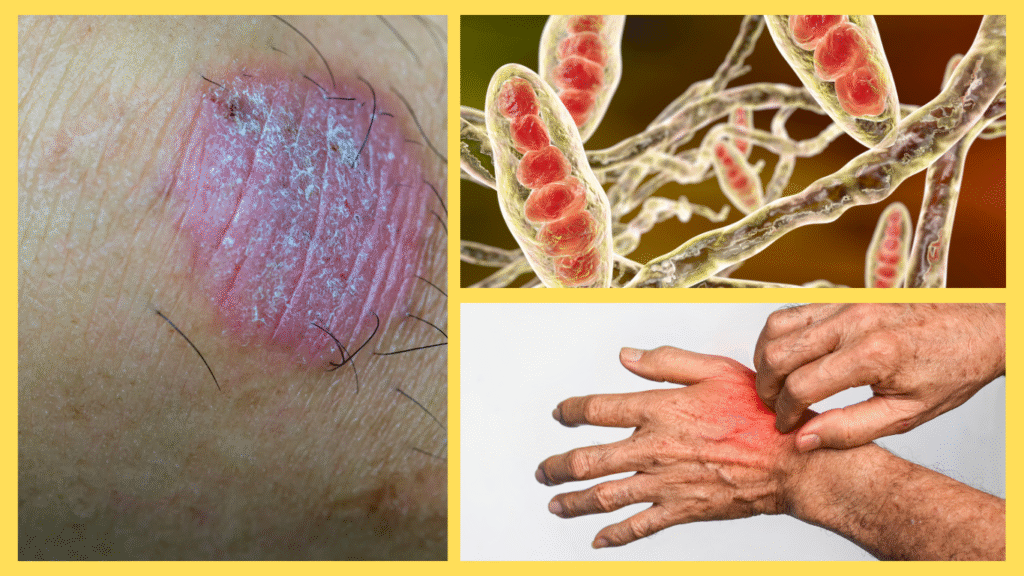

Step inside the world of ringworm, a skin-loving fungus that causes red, itchy rashes. Discover where it originated, how it spreads, and how to stop it.

The morning feels warm and slightly damp—the kind of environment I love most. My name is Trichophyton, but humans usually call me ringworm. That name confuses many people because I am not a worm at all. I am a fungus, closer to the molds that grow on bread than to any insect or parasite. My favorite home is the outer layer of human and animal skin, especially in places where sweat and heat mix. Skin, hair, and nails all contain keratin, a strong protein that gives structure and protection, and keratin happens to be my food of choice (CDC).

I have been around for centuries. Ancient medical texts from Asia, Africa, and Europe describe outbreaks of red, circular rashes spreading quickly in communities. Back then, people didn’t understand what I was. Some thought I was caused by curses, others by worms crawling beneath the skin. Over time, I learned to adapt to many different hosts. I can survive on humans, dogs, cats, cattle, and even horses. My spores are tough and patient, able to wait on clothing, bedding, or soil until a new host comes along. Today, I am found worldwide, though I thrive most in warm, humid regions where people and animals live closely together (NIH).

The moment I land on fresh skin, I begin my quiet work. Maybe a child hugs a kitten already carrying me. Maybe an athlete shares a towel after practice. Maybe someone slips bare feet into public shower stalls where I linger on damp floors. However I arrive, I cling to the skin and settle in. My spores germinate, sending out delicate filaments called hyphae. These branch outward, forming colonies that burrow into keratin. To the naked eye, this process is invisible at first. The skin looks normal, and the host feels nothing unusual. But inside, I am carving my territory.

Slowly, a ring begins to form. My outer edges are the most active, so as I expand outward, the center starts to clear. What appears on the skin is a raised, red border shaped like a circle, often scaly or itchy. It is this shape that gave me my misleading name: ringworm. People scratch at the irritation, and every scratch helps me. Fingernails carry me to new areas of skin, spreading the infection further. Clothing traps warmth and sweat, creating an ideal greenhouse where I can multiply. On the scalp, I sometimes create bald patches where hair breaks off. On the feet, I become what humans call athlete’s foot. On nails, I turn them thick, brittle, and yellow. And I am not alone—my cousins Epidermophyton and Microsporum cause similar infections, each choosing their favorite part of the body (Mayo Clinic).

But life is not without challenges. The human body notices me eventually. White blood cells rush to the site, sparking inflammation. This immune reaction creates redness, swelling, and more itching. For me, this is simply the cost of living on skin. I can hold on for weeks or even months if untreated, but humans rarely stay passive forever.

When itching grows unbearable or the rash becomes visible to others, people act. Some visit a pharmacy for antifungal creams, sprays, or powders. These treatments seep into my filaments and break down my protective walls, making it impossible for me to grow. If I am on the scalp or nails, I face an even stronger weapon: antifungal pills. These medicines travel through the bloodstream and attack me from the inside out. With consistent treatment, I usually cannot survive beyond two to four weeks. However, if a person stops treatment too soon, I may return. My spores are patient, and I know how to wait for another chance (CDC – Treatment).

Of course, not every infection begins with humans. Many times, I hitch a ride on animals. Kittens and puppies are common carriers because their immune systems are still developing, and their playful habits spread me quickly. Farmers who handle cattle and horses also give me opportunities to cross from one species to another. In poor or crowded communities where people share clothing or bedding, my reach grows faster. Children are especially vulnerable because they play closely together, share combs, and spend more time with pets. This is why schools, gyms, and animal shelters often see outbreaks.

Though I am skilled at spreading, I am also easy to prevent. Humans have developed simple but effective defenses. Washing hands after touching animals, keeping skin dry, wearing sandals in locker rooms, and avoiding shared personal items like towels or hairbrushes all make it harder for me to travel. In places where hygiene improves, my presence fades. Yet in regions where healthcare is limited, I continue to thrive, feeding silently on keratin and leaving behind my telltale rings.

As evening falls in the life of my host, I reflect on the delicate balance between humans and microbes like me. I am not as deadly as bacteria that cause pneumonia or viruses that spark pandemics, but I am stubborn. I bring discomfort, social embarrassment, and sometimes long-lasting damage to nails and hair. My story is not about sudden danger but about persistence. I remind humans that even small, overlooked organisms can cause big interruptions in daily life.

And yet, I also highlight something else: resilience. Humans have learned to recognize me, to treat me, and to share knowledge across generations. Ancient physicians once misidentified me as a worm, but modern science has exposed my fungal identity and revealed my weaknesses. Every tube of antifungal cream on a pharmacy shelf is proof of how far humans have come in understanding the invisible world that surrounds them.

So, the next time someone notices a red, itchy ring on their arm or a pet with a patch of missing fur, they will know it is me. I am ringworm, a fungus with a long history and a simple goal: to find keratin and survive. My day may begin on the skin of a child, a kitten, or a farmer, but it often ends in defeat when humans take action. In my story, the real lesson is clear—prevention and awareness are just as powerful as medicine. Because when people pay attention to the little things, even fungi like me cannot stand in their way.

Sources