Step inside the story of Clostridium botulinum, the microbe behind botulism. Learn how it thrived in food for centuries, why it was once so feared, and how science finally turned the tide.

The world is dark, silent, and full of waiting. I am Clostridium botulinum, a bacterium unlike most others. My life begins in the soil, where I lie dormant as a spore. In this state, I am nearly indestructible. I can resist sunlight, drought, and even chemicals. Sometimes I drift into riverbeds or cling to dust. Other times I find my way into the cracks of vegetables, meat, or fish. Wherever I go, I wait for the right environment.

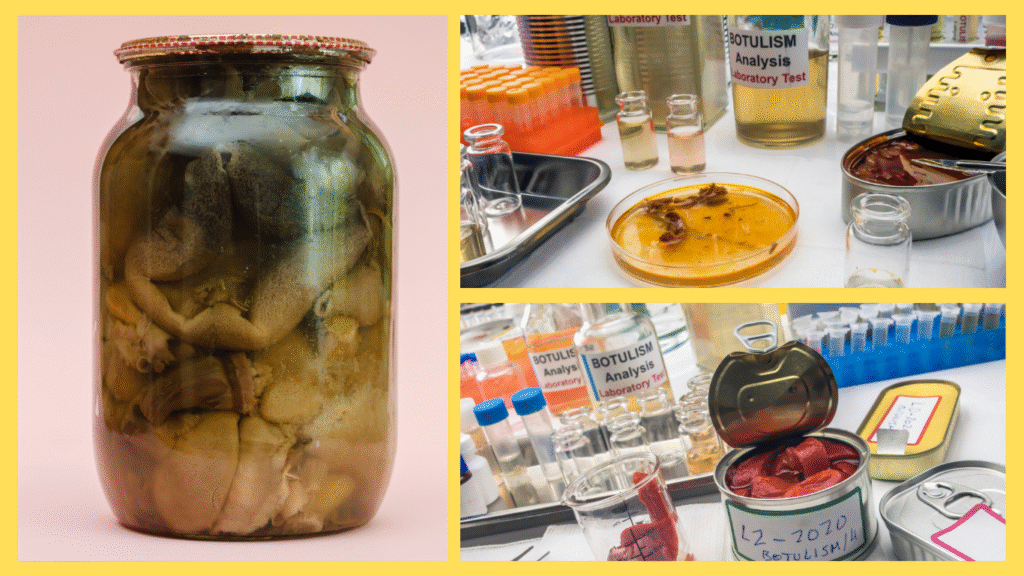

When oxygen surrounds me, I remain still. But when the world turns airless, wet, and warm, I come alive. I awaken from dormancy and begin to grow, multiplying in places where humans least expect me: sealed jars, smoked meats, and tightly wrapped fish. It is in these conditions that I unleash my secret weapon: a toxin that has killed more people than I can count. My toxin is silent, tasteless, and invisible. A single drop could wipe out a village.

Long before scientists gave me a name, humans already feared me. In the 18th and 19th centuries, outbreaks struck without warning. Families gathered around a table, sharing smoked sausages or salted fish. Hours later, one by one, they felt their eyelids droop. Their speech slurred, their muscles weakened, and panic set in as they struggled to breathe. For many, it was too late. Death came quietly but swiftly, and no one knew why. They blamed the food, sometimes the butcher, sometimes even curses. But the truth was simpler: I was there, multiplying in their meals, turning nourishment into poison.

Inside the human body, I act differently from most microbes. Unlike bacteria that grow inside the gut and spread, I let my toxin do the work. Once swallowed, my poison enters the bloodstream and reaches the nerves. It blocks the release of acetylcholine, a chemical that carries messages from nerves to muscles. Without this signal, muscles stop moving. The paralysis begins in the face, causing double vision and drooping eyelids, then creeps downward to the arms, chest, and legs. The cruelest part is that the mind stays clear. Victims know exactly what is happening, but they cannot call for help, cannot move, cannot even breathe on their own. Before modern medicine, the fatality rate for foodborne botulism was more than 60% CDC.

Back then, doctors were helpless. They saw patients losing strength hour by hour. Some tried bloodletting, others herbs, but nothing worked. Many described the strange illness as “sausage poisoning,” since outbreaks often followed poorly preserved meats. Others thought evil spirits had cursed their meals. It was not until the early 19th century that someone finally began to piece the mystery together.

Dr. Justinus Kerner, a German physician, noticed the connection between sausages and this peculiar paralysis. He carefully studied cases and performed experiments, even on himself, to understand the toxin. He described how the poison worked and warned that it blocked nerve function. Remarkably, Kerner suggested that this deadly toxin might one day be used for medicine, to calm overactive nerves. His words proved prophetic, though he could not have known it at the time. He had uncovered the shadowy world where I thrived, and his work was the first step in stripping away my invisibility.

Still, for decades, I remained a terrifying killer. Villages fell ill after community feasts, soldiers grew weak after eating preserved rations, and families suffered tragedy from homemade canned goods. Humans had not yet discovered safe canning, refrigeration, or sterilization. Without oxygen, in tightly sealed jars and smoked meats, I thrived. I spread easily, leaving behind grief and confusion.

When scientists finally isolated me, they discovered the conditions I loved most: no oxygen, warmth, and a sealed environment where I could grow undisturbed. They also discovered how to stop me. Heat strong enough to reach 121°C (250°F) under pressure destroys my spores. That is why pressure canning became so important for preserving food safely. Later, refrigeration and preservatives added more layers of defense. Once these practices spread, I lost my grip on households and communities. Outbreaks grew rarer, though they never disappeared entirely Mayo Clinic.

For humans, understanding me was a turning point. They realized that my spores could be present in soil and dust all around them, invisible yet everywhere. They learned that even honey could contain spores, which is why infants should never consume it. Babies do not yet have the gut defenses to fight me, so I can grow inside them and release my toxin from within. This form, infant botulism, became another reminder of how powerful I could be in the smallest of ways.

But my story has another twist. The very toxin that once terrified humanity eventually became one of their most surprising medical allies. Under strict control, in tiny doses, doctors learned how to use botulinum toxin to help patients. It could relax muscles in people with spasms, ease chronic migraines, and even smooth wrinkles. What was once a killer became a treatment, transforming fear into innovation NIH.

Still, history remembers me not for medicine but for the devastation I caused before discovery. Imagine a time when a simple dinner could kill half a family, when no one understood the invisible force at work. I was one of the deadliest threats hidden in food. Silent, odorless, and without warning, I paralyzed communities long before science found a way to fight back.

The fight against me is not over. Even today, outbreaks occur when people ignore basic food safety. Home-canned vegetables that are not heated properly, fish that is preserved without enough salt, or leftovers left unrefrigerated too long can still give me a chance. However, now humans know what to look for. They are taught never to eat from bulging cans, to heat food thoroughly, and to refrigerate promptly. They have antitoxins that can neutralize my poison if given quickly, and ventilators to keep patients alive until the toxin fades. What was once a death sentence can now be survived.

From my perspective, I am only doing what I was designed to do: survive, multiply, and protect myself. I did not choose to be deadly, but my toxin gave me a power that shaped human history. I thrived on neglect, ignorance, and poor preservation methods. Yet humans are resourceful, and once they understood me, they stripped away much of my mystery.

My story, however, is a warning that knowledge is fragile. If people grow careless, if food safety is ignored, if preservation is rushed, I can return. I still wait in soil, dust, and rivers, patient as ever. I will always be there, silent and invisible, watching for the chance to awaken. But for now, I live as a shadow of what I once was, remembered as the microbe that taught humans the importance of science, vigilance, and respect for the unseen.

Health message: Clostridium botulinum remains one of the deadliest microbes known to humans, but it is also one of the most preventable. Proper food handling, pressure canning, refrigeration, and hygiene protect families from botulism. Knowledge once turned fear into control, and it remains the strongest defense against this silent killer.