Discover the day-to-day life of Helicobacter pylori, the bacteria behind stomach ulcers and bleeding. Learn how it survives, causes disease, and what fights back.

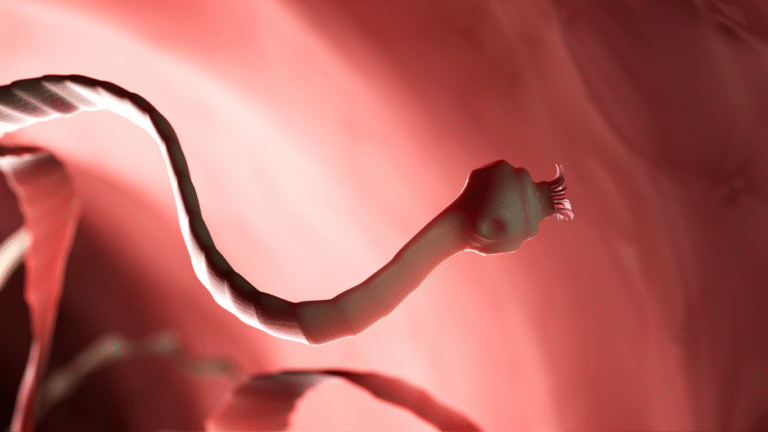

I wake to a storm of acid. I am Helicobacter pylori, a spiral-shaped bacterium living deep in the human stomach. My world paddles through curdled acid and protective mucus. To many microbes, this place is deadly. But this is home for me–an environment I’ve evolved to survive in.

Life inside the stomach is a delicate balance of danger and opportunity. Despite the corrosive acid that breaks down food, I’m shielded by a cloud of mucus that clings to the stomach walls. Here, the pH dips low, nearly at zero, yet I persist–thanks to my most important tool: urease. I break down urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide, neutralizing acid around me and carving out a safe pocket to rest and multiply (NIH overview of pathogenesis).

I move with purpose, spinning through mucus using my flagella. They are like tiny tails. With them, I navigate toward the tranquil lining of stomach cells. There, I cling tightly using special adhesins–BabA and SabA–that latch onto sugars on the cell surface (Wikipedia details on adhesins). This anchoring keeps me from being washed away with every acidic wave.

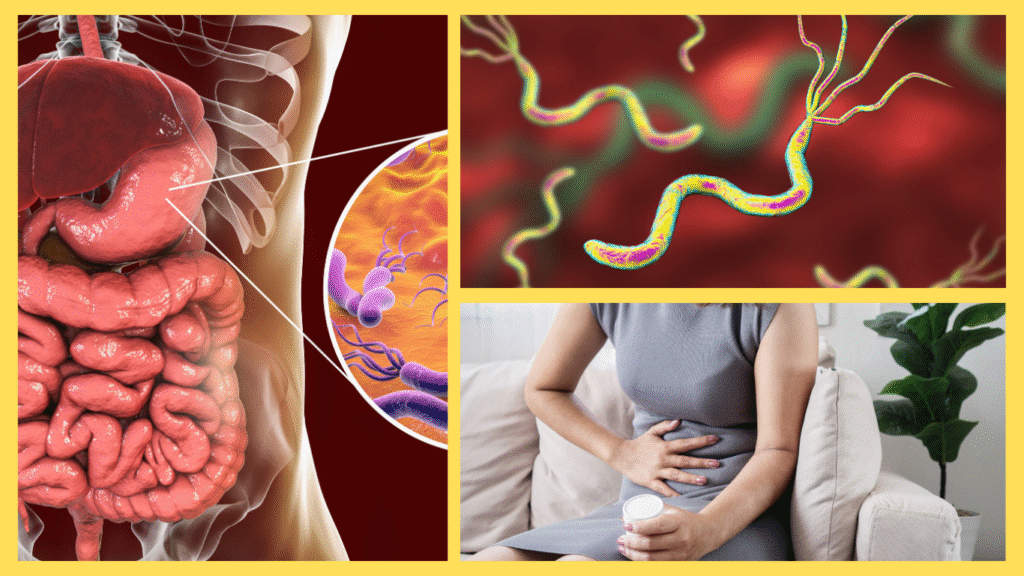

Once attached, I begin to colonize. I reproduce slowly but steadily, forming groups that defend against the immune system. I release toxins like CagA and VacA that damage cells and incite inflammation. This unsettles the stomach lining, causing it to swell, bleed, or break down over time–the start of ulcers and pain (PMC on infection steps; StatPearls overview of ulcer cause by H. pylori) NCBI.

Meanwhile, the human doesn’t notice the drama at first. They may feel mild discomfort or no symptoms until the damage grows. In most cases of peptic ulcer disease—up to 90%—I am the cause behind those painful sores in the stomach lining or the upper intestine, the duodenum (CDC fact sheet on ulcer causes) CDC.

As I burrow deeper into the lining, I disrupt mucous protection and interfere with bicarbonate release. I manipulate cells, making them more vulnerable to stomach acid. The result is a sore—a stomach ulcer. Once an ulcer bleeds, blood can slip into the digestive tract, showing up in vomit or stool. In some cases, the blood is hidden but detectable by tests, a sign of serious damage. Meanwhile, the body’s response—immune cells, inflammation, and repair attempts—adds to the pain and swelling (NIH and Mayo Clinic info on gastritis and ulcers) Mayo ClinicPMC.

Yet, humans are not defenseless. When stomach pain becomes too intense, the doctor may run tests. These include breath tests, stool antigen tests, or endoscopy. Once I’m detected, doctors send in a team—usually a mix of antibiotics and acid blockers—to flush me out. Treatment works well for most people. Without eradication, however, I quietly persist, rebuilding my colonies and continuing the cycle (CDC guidelines) CDC Stacks.

Even as humans fight back, I’m not ready to give up. I form biofilms—structured groups fortified by protective slime. These biofilms reduce my exposure to antibiotics and the immune system, giving me the ability to survive and resist. I can even slip into a hibernation-like state to wait out hostile conditions, then return when the coast is clear (PMC on H. pylori biofilms) PMC.

On rare but tragic occasions, I can slip through chronic inflammation and one step further—pushing humans into risk of gastric cancers and rare lymphomas. That is why in 2014 WHO advocated eradicating me to reduce gastric cancer mortality (PMC review) PMC.

By evening, this day-of-invasive chaos either ends with me driven out by treatment or persists quietly, lining ulcers and inflaming tissue. Even without dramatic bleeding, continual inflammation can harm over time. Most of the time, life returns to “normal,” but the threat lingers until a complete cure is achieved.

This journey teaches humans an important lesson: what starts as a tiny hidden infection can lead to serious consequences. Peptic ulcers and bleeding are not accidents—they are symptoms of a battle between microbes and body. Prevention starts early with clean water, avoiding poorly sanitized utensils, and testing childhood infections where risks are high (Mayo Clinic prevention tips) Mayo Clinic.

I am Helicobacter pylori. My day starts with survival in acid, continues with stealthy colonization, progresses through inflammation and ulcer formation, and either ends with cure or prolonged damage. Humans may not see me with their eyes, but I can leave marks that last a lifetime. That is why science, medicine, and hygiene must strike first.

Sources

- CDC – Peptic Ulcer Causes: H. pylori responsible in nearly 90% of cases CDC

- NIH (StatPearls) – H. pylori causes inflammation and ulceration NCBI

- Mayo Clinic – H. pylori symptoms, causes, and prevention Mayo Clinic

- PMC Overview – Steps of H. pylori colonization and pathogenesis PMC

- PMC Review – H. pylori pathogenesis and link to ulcers and cancer PMC

- PMC on H. pylori biofilms and antibiotic tolerance PMC