Discover the effect of rabies on animals and humans in a narrative journey through the rabies virus. Learn how it spreads, its dangers, and prevention.

The night is cool, and I drift quietly in the saliva of a stray dog. I am the rabies virus, small, bullet-shaped, and invisible to the naked eye. My world is made of teeth, gums, and the warm rhythm of panting breath. For me, this host is home. I thrive in wild animals like raccoons, foxes, and bats, and in domesticated animals such as dogs and cats when they aren’t protected by vaccines. In these creatures, I have found ways to survive for centuries, quietly spreading through bites, scratches, and saliva.

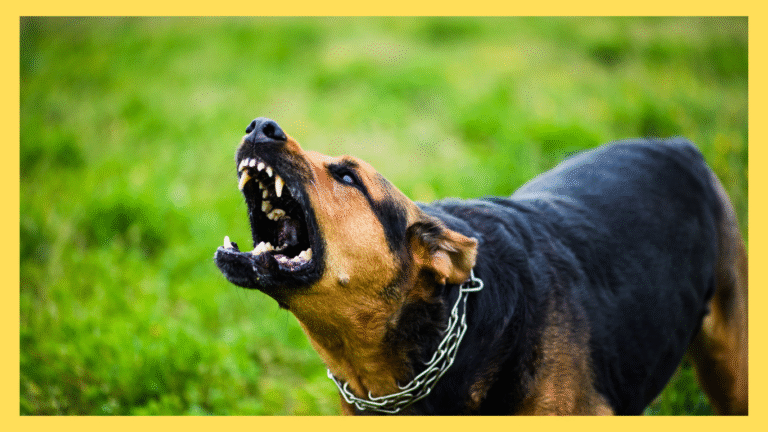

But tonight is different. My host, restless and uneasy, growls at a shadow. He lunges, and his sharp teeth sink into the leg of a passing human. In that single moment, my journey takes an accidental turn. I leave the body of the animal I know so well and enter the bloodstream of a species I was never designed to inhabit. For the human, it seems like just a small wound. For me, it is the start of a race against time.

The puncture marks close quickly, and the bleeding may not even look severe. But through that tiny gap in the skin, I slip into new territory. I don’t thrive in blood the way bacteria do. I need nerves, and nerves are everywhere beneath the skin. I attach to them, almost invisible, and begin my slow crawl inward. Most infections announce themselves with fevers, swelling, or pus. I do none of these things at first. Instead, I move quietly, traveling along nerve fibers at about 100 millimeters a day (CDC). The person may think the bite is harmless, perhaps just a scratch from an irritated dog. They may rinse it briefly or ignore it altogether. But even as they walk away, I am already on the move.

What makes me dangerous is not just my speed but my invisibility. The immune system is built to fight invaders in the bloodstream, detecting threats and sending white blood cells to battle. But I don’t linger in blood. Instead, I use the nervous system like a hidden highway, one where defenses are weaker and slower to respond (NIH). This is why I am so feared. Days, weeks, or even months may pass without any sign that I am there. And yet, the entire time, I am advancing toward the spinal cord and brain.

Once I reach the brain, my quiet journey ends. I multiply rapidly inside neurons, the very cells that control thought, memory, and behavior. With every round of replication, my host changes. In the dog who bit, aggression grows. Fear, confusion, and agitation replace calmness. He snarls at shadows, snaps at hands that once fed him, and lashes out at other animals. This is “furious rabies,” one of my most effective strategies for survival. By driving my hosts into fits of biting, I guarantee that I spread to the next victim.

Not every infection looks the same. Sometimes, instead of aggression, I trigger paralysis. Muscles weaken, drooling increases, and swallowing becomes difficult. In both cases, death is almost certain once symptoms appear (Mayo Clinic). For animals, there is rarely any return once the disease reaches the brain. In humans, too, the odds are grim. Rabies remains one of the deadliest infections known to medicine, with almost 100% fatality once clinical signs develop (WHO).

But there is a turning point, and it depends on timing. If a person bitten by a rabid animal seeks care right away, my journey can be stopped. Doctors wash the wound thoroughly, often with soap and water, which can physically remove many of my particles. Then, the real defense begins. They administer the rabies vaccine and, in some cases, rabies immune globulin. The vaccine trains the immune system to recognize and attack me, while the immune globulin provides immediate antibodies that start working instantly (CDC). If given early enough, these defenses build a wall in my path, preventing me from reaching the brain.

But every hour matters. The longer the delay, the closer I get to the nervous system’s control center, where no vaccine or medicine can reach me in time. Once fever, anxiety, or hallucinations begin, there is almost nothing medicine can do. This is why rabies prevention is so essential, both for humans and animals.

In animals, vaccination is the key. Dogs and cats that receive regular rabies shots not only stay healthy but also block my route to humans. Countries that have enforced widespread dog vaccination programs have drastically reduced human rabies deaths. In fact, more than 95% of human rabies cases worldwide come from dog bites in regions where vaccination is not universal (WHO).

The effect of rabies on animals and humans is not only physical but also emotional and social. Families lose pets they love, farmers lose livestock, and communities lose people to a disease that is almost entirely preventable. I am powerful, but I am also fragile when confronted with awareness and preparedness. A vaccinated pet stops me in my tracks. A cautious traveler who avoids contact with wild animals blocks my path. A parent who teaches their child to seek help after an animal bite writes the end of my story before it can begin.

In the stray dog who carried me at the start, the fight is lost. His muscles twitch, his eyes glaze, and he collapses. For him, there is no rescue. But the human he bit is fortunate. Their wound was treated, and vaccines were given in time. I cannot move forward, and my journey ends here.

What makes me both tragic and unique is that I am almost entirely preventable. Unlike many infections that are difficult to stop, I can be blocked with vaccines, education, and simple medical care. Yet every year, tens of thousands of people—especially children in parts of Asia and Africa—still die from rabies. Most of them never received treatment in time. Most of them could have lived if awareness and vaccines had been available.

So, what lesson remains? Rabies is devastating, but it does not need to be. With proper animal vaccination, quick medical care after bites, and global awareness, the cycle of infection can end. For me, the rabies virus, silence is my greatest ally. I thrive on neglected wounds, unvaccinated pets, and dismissed dangers. But where knowledge spreads faster than I do, my story ends before it has a chance to begin.

✅ Key Sources for Facts: