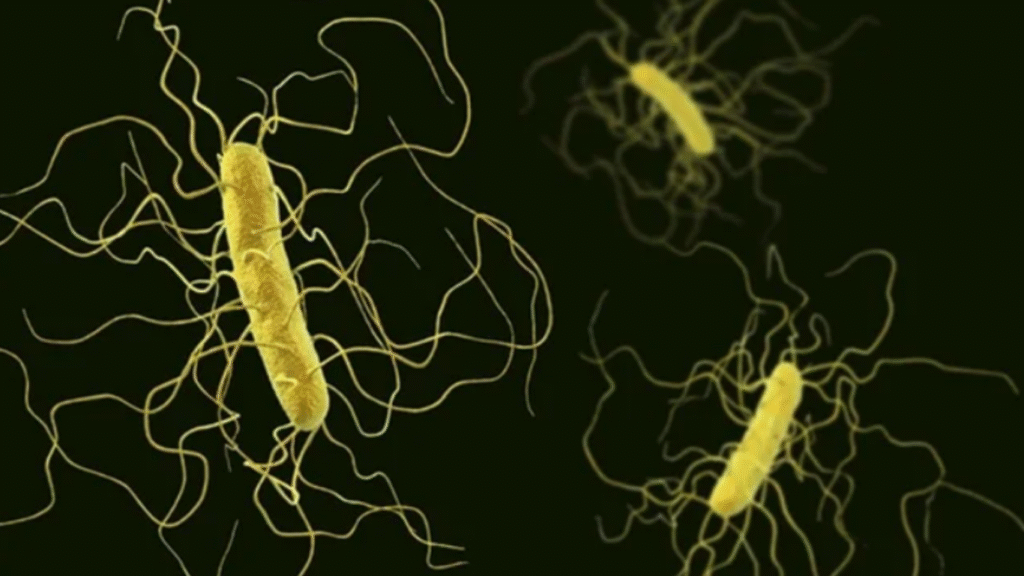

Step inside the microscopic world of Clostridioides difficile. Learn how this hidden invader thrives, what triggers it to cause serious illness, and how to prevent infection.

The morning begins in silence, but for a dog carrying Clostridioides difficile, or C. diff, the quiet doesn’t last long. Inside the gut, where trillions of bacteria normally work in harmony to help digest food and protect against invaders, something has gone terribly wrong. A sudden imbalance has allowed C. diff to thrive, releasing toxins that irritate and inflame the intestinal lining. For the dog, it starts with an uncomfortable shift in the stomach, a restless night of tossing and turning on the floor, and then sudden diarrhea that leaves both pet and owner concerned.

As the day progresses, the infection tightens its grip. The dog refuses breakfast, turning away from a bowl it once emptied in seconds. A mild fever develops, its body trying to fight back. The stool is watery, sometimes streaked with mucus or blood, and the dog strains as if relief is always out of reach. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the toxins produced by C. diff are what make the infection so dangerous—they inflame the colon and disrupt the delicate balance of bacteria that normally keep the gut healthy (CDC).

For dogs, the story often begins after a course of antibiotics. Medications prescribed for another illness may wipe out helpful bacteria, leaving behind an open battlefield where C. diff takes over. Veterinarians note that not every dog exposed to the bacteria will get sick; many may carry it silently. But when symptoms appear, they can be severe, requiring immediate medical care to prevent dehydration and further complications. The Mayo Clinic emphasizes a similar point in humans: antibiotics like clindamycin, cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones can increase the risk of infection (Mayo Clinic).

By mid-morning, the dog is lethargic, curling up in corners, avoiding play, and gazing at its owner with dull, tired eyes. What once felt like a normal day quickly turns into one filled with worry. The owner wonders if it’s something minor—perhaps bad food or stress—but the persistence of diarrhea signals something more dangerous. In veterinary clinics, stool tests are used to detect the presence of C. diff toxins. The diagnosis is often unsettling, because while most cases can be treated, the infection has a reputation for being stubborn and sometimes recurring.

Meanwhile, humans in the household may wonder about their own risk. C. diff is well known in hospitals and nursing homes, where vulnerable patients are exposed to contaminated surfaces or spread through hand-to-hand contact. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) highlights that spores can live for months on objects like bedding, floors, or even pet bowls, making disinfection crucial (NIH). While transmission from dogs to humans is rare, the possibility exists, and it underscores the importance of hygiene—washing hands thoroughly, cleaning with bleach-based solutions, and isolating infected pets during treatment.

By afternoon, the veterinarian begins treatment. The dog receives fluids to replace what has been lost and medication to target the infection. In both humans and dogs, the antibiotic metronidazole or vancomycin may be prescribed, but their use must be carefully managed. Overuse can worsen resistance, creating strains of C. diff that are even harder to treat. Some cases require newer therapies, such as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), where healthy bacteria from a donor are introduced to restore balance. Though more common in human medicine, the principle highlights just how critical gut health is in overcoming the infection.

As the hours drag on, the dog’s condition is closely monitored. Owners disinfect everything it touches, aware that spores can cling to fur, paws, and surfaces. The smell of bleach lingers in the air, mingling with the sound of the dog’s restless breathing. Outside, life continues as usual, but inside the home, there is a heightened sense of vigilance. Every trip outdoors to relieve itself is followed by careful cleaning, every water bowl scrubbed until spotless.

Evening brings a mix of exhaustion and cautious hope. If the dog shows improvement—drinking water, wagging its tail faintly—the relief is palpable. Yet the owner knows recovery may not be quick. According to the CDC, one in six patients treated for C. diff will experience a recurrence within two to eight weeks (CDC). This stubborn cycle is part of why prevention is emphasized so strongly. For dogs, preventing infection means using antibiotics responsibly, ensuring environments are kept clean, and seeking veterinary care at the first signs of trouble.

As night falls, the house quiets again, but the day’s events linger in memory. The dog lies curled up in its bed, resting after a long, difficult day. The owner reflects on how something so small—a bacterium invisible to the eye—can disrupt life so profoundly. The infection doesn’t just affect the body; it affects routines, emotions, and the deep bond between human and animal. In that moment, science feels less like an abstract field and more like a lifeline, offering explanations, treatments, and most importantly, hope.

What C. diff reminds us—whether in dogs or humans—is that health is fragile and interconnected. Our choices, from how we use antibiotics to how often we wash our hands, ripple outward in ways we might not always see. Caring for a pet becomes not just an act of love but an act of vigilance, a partnership in maintaining balance. And when that balance falters, it is science, informed by research from places like the CDC, NIH, and Mayo Clinic, that guides the way back to health.

Sources: