Step into the shoes of HIV for a day. Discover how the virus lives, spreads, and affects the human body, and learn why early prevention and treatment matter.

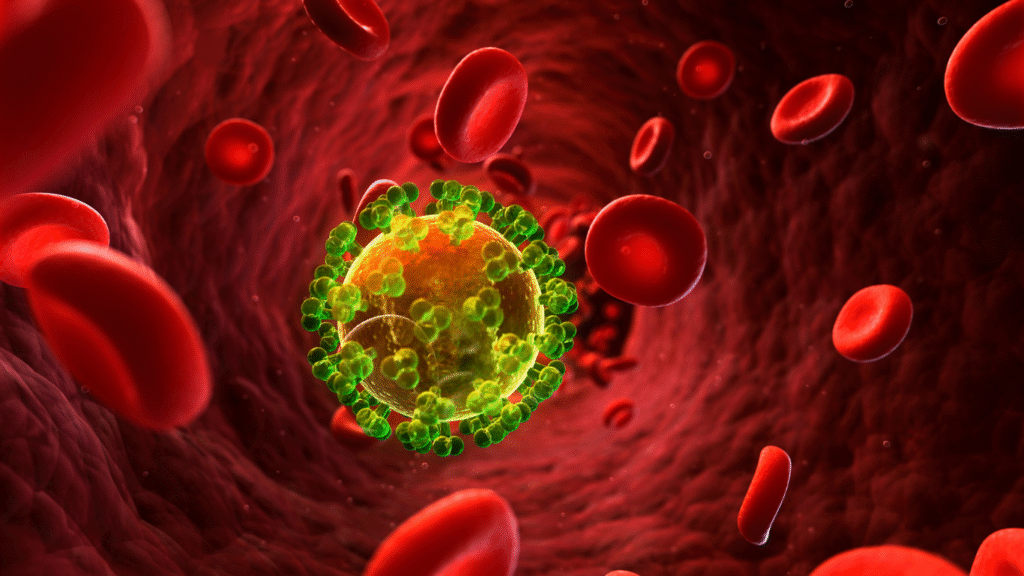

It is warm, dark, and endlessly moving here in the bloodstream. I am HIV — Human Immunodeficiency Virus, a microscopic intruder designed for survival. My home is unlike a human’s cozy house. It is a river of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets rushing through twisting vessels. I drift quietly, blending in, unnoticed. I know what I am searching for: a CD4 T-cell, one of the immune system’s most important defenders (CDC). For now, life is calm, but I am patient. The immune system does not yet realize I am here. Soon, though, everything will change.

As I travel, I spot my target. The CD4 T-cell moves gracefully, unaware of what awaits it. Normally, this cell would be leading the defense against dangerous bacteria and viruses, coordinating troops of other immune cells to protect the human body. But for me, this cell is the perfect host, a shelter and a factory rolled into one. With proteins on my surface, I latch on tightly. Then, using clever tricks evolved over countless generations, I slip inside. Once I am hidden within, I begin rewriting the cell’s instructions. My RNA becomes DNA through an enzyme I carry called reverse transcriptase, and then I stitch myself permanently into the cell’s genetic library. Suddenly, the CD4 T-cell is no longer serving its master. It is serving me.

The cell starts following my commands, and instead of producing healthy proteins to protect the body, it builds endless copies of me. One by one, my siblings bud off from the surface of the cell and scatter into the bloodstream, each seeking out more CD4 T-cells to infect. Slowly but surely, the host’s own army is being turned against itself. The human feels nothing at first. This is how I survive best — silently, without warning. Weeks, months, even years can pass before any signs appear. But while the person goes about their life, I am multiplying, gradually reducing the number of CD4 cells little by little (Mayo Clinic).

The damage builds quietly. Normally, CD4 cells direct defenses against invaders, sounding alarms to recruit antibodies and killer cells to fight infections. Without enough of them, even common germs — the type that would barely bother a healthy person — can become dangerous. Over time, if I remain unchecked, I can push the body into a weakened state called AIDS, or Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. In this stage, illnesses that were once harmless — pneumonia, fungal infections, certain cancers — become life-threatening (CDC).

But my story is not always so smooth. Humans have learned to fight back. Some have even been born with a rare advantage. A tiny fraction of people carry a genetic mutation called CCR5-delta32, which makes it much harder for me to enter their CD4 cells. I depend on receptors like CCR5 to slip inside, and without them, my journey ends before it begins. These individuals are naturally resistant, and while they are rare, their existence proves that nature itself can build barriers against me (NIH). For me, encountering one of them is like a locked door with no key. I drift helplessly past, unable to take hold.

For everyone else, however, I am still a threat. Once inside the body, I spread through blood, semen, vaginal fluids, and breast milk. This is why certain activities — like sharing needles or having unprotected sex — give me the perfect opportunity to move from one host to another. Yet humans are not powerless. Knowledge has given them tools to reduce my reach. Protective measures such as condoms, clean needle programs, and preventive medicines like PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) block my path effectively when used correctly (CDC).

Still, when I do gain entry, the real battle begins. Eventually, the human body starts to notice something is wrong. Fatigue creeps in. Fevers, night sweats, and swollen lymph nodes raise suspicion. But just as the symptoms start appearing, the human’s defense system receives reinforcements in the form of medicine. This is when my day takes a dramatic turn.

A group of powerful drugs enters the bloodstream — antiretroviral therapy (ART). These medicines don’t destroy me directly, but they make every step of my process difficult. One drug blocks me from entering CD4 cells. Another stops reverse transcriptase from turning my RNA into DNA. Yet another prevents my proteins from assembling into new viruses. Suddenly, my once steady expansion screeches to a halt. My numbers shrink. The CD4 cells begin to recover, and the immune system regains its footing (CDC).

From my perspective, it feels like being trapped in quicksand. Every attempt to move is blocked. Every effort to multiply fails. The humans have found a way to suppress me, not just for a day, but for years if they remain faithful to their treatment. Even more frustrating, when my levels drop low enough in the bloodstream, they become undetectable on medical tests. This means that while I may still linger, I can’t be passed on through sexual contact. “Undetectable equals untransmittable,” the scientists call it — or simply, U=U (NIH). For me, this is defeat.

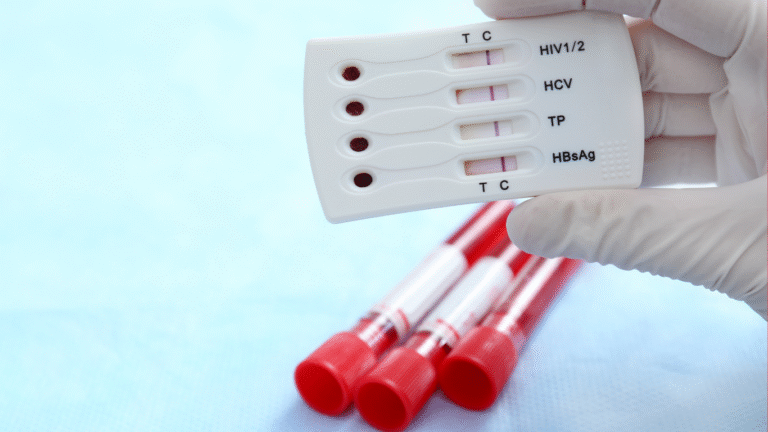

Yet, despite the progress, I remain dangerous when ignored. Without regular testing, many humans discover me too late, when I have already weakened their defenses. That is why health experts urge people to get tested at least once in their lifetime, and more often if they are at higher risk. Early detection changes everything. With treatment, my hosts can live long, healthy lives, raising families, working jobs, and enjoying decades of life. Without it, my day can turn into years of destruction.

As I fade into the background under the weight of medicine, I reflect on my strange existence. I began this journey silently, drifting unnoticed in the bloodstream, then latching onto my favorite cells and turning them into factories for my replication. I thrived in shadows, weakening the body little by little, until science intervened. For me, ART is a roadblock I cannot escape, a constant reminder that human knowledge has evolved faster than my tricks.

For the human, however, the message is clear: HIV is not invincible. Prevention, testing, and treatment together form a powerful shield. Safe practices keep me from spreading. Regular screenings catch me early. Consistent medicine holds me down so tightly that I cannot escape. And in rare cases, the very code of human DNA itself — like the CCR5-delta32 mutation — closes the door before I can even begin.

So the takeaway from my day is simple. I may be HIV, and I may have once been feared as unstoppable, but the truth is that science and prevention have changed the story. I am still here, drifting in the bloodstream, always looking for a new host, always trying to survive. But with vigilance, education, and care, humans can ensure that my day never turns into theirs.