Discover how papillomavirus causes HPV warts in humans and horn-like growths in rabbits, inspiring cancer research and the jackalope legend.

I wake in a snug, shadowed corner of human skin, tucked under the edge of a fingernail where the warmth never fades and the air never changes. I am a papillomavirus—small, quiet, invisible to the naked eye. Here, the skin cells bustle about their business, dividing and replacing each other in a calm, predictable rhythm. Life in this neighborhood is steady, almost serene. But I know my peace will not last.

The vibrations begin first—a brushing touch, the heat of another hand. It’s a handshake, a brief moment of contact, and it’s all I need. The skin of my current home grazes against a new one, and in that instant, I am free, riding the invisible bridge between bodies. My landing spot is perfect: a nearly invisible nick in the surface, no wider than a hair. This is my doorway.

I slip in without ceremony. My destination is the layer of skin cells that are busy dividing, replacing what’s been worn away by the day. These cells are factories, and I know exactly how to take over their machinery. I settle inside one, quiet at first, letting the cell keep its routine until I’m ready. Then I begin copying myself—swiftly, efficiently, without asking permission. Soon, the changes ripple outward. The skin thickens, cells pile on cells, and a small, raised bump forms. To the human, it’s just a wart. To me, it’s a thriving city of my own kind.

Many of my human relatives—human papillomavirus, or HPV—are harmless squatters, causing only these small growths on fingers, feet, or around the mouth. But in other cases, my cousins find their way into more delicate tissues, lingering for years and sometimes contributing to cancers such as cervical cancer. Most humans don’t realize how long we can wait, quietly embedded in cells, until their immune system notices and begins to push us out.

Meanwhile, far from human skin, I sometimes wake in an entirely different world. Here, the ground is soft with meadow grass, and my host is not a person but a rabbit—a wild cottontail or a pampered domestic bunny. In this form, I am the Shope papillomavirus, and my work looks very different.

I might enter through the bite of a mosquito or flea, carried from one rabbit to another. My journey through the skin is much the same—find a dividing cell, take over, begin my work—but the results are spectacular. Instead of small, flat warts, I build towers of keratin that rise from the skin like twisted horns. They may sprout from the head, the ears, even the eyelids, curling into shapes that look almost mythical. Humans call these rabbits “horned rabbits,” or even claim they are the fabled jackalope.

Back in my human hosts, life is more dangerous for me. If the immune system catches wind of my presence, white blood cells arrive like detectives, releasing proteins that jam my copying process. Specialized T-cells may target the infected skin cells themselves, destroying my shelter. Sometimes, the human calls in reinforcements—cryotherapy to freeze me out, salicylic acid to peel away my stronghold. For warts on the feet or hands, persistence usually works; eventually, I’m chipped away until nothing is left but smooth skin.

In rabbits, my story often plays out differently. Wild ones usually recover after a few months; their immune system recognizes me and begins to shrink the keratin horns. But sometimes my growths interfere with eating or vision, making life harder for my host. In those cases, without help from a veterinarian, the rabbit may weaken. In rare cases, my growths can even turn cancerous, especially if they linger too long.

My existence might have gone unnoticed forever if it weren’t for a curious scientist named Dr. Richard Shope in the 1930s. Hunters had brought him strange-looking rabbits from the American Midwest—rabbits with long, horn-like structures protruding from their heads. Shope studied the growths, ground them into a paste, and injected it into healthy rabbits. When horns grew there too, he had his answer: a virus was behind the transformation. That virus was me.

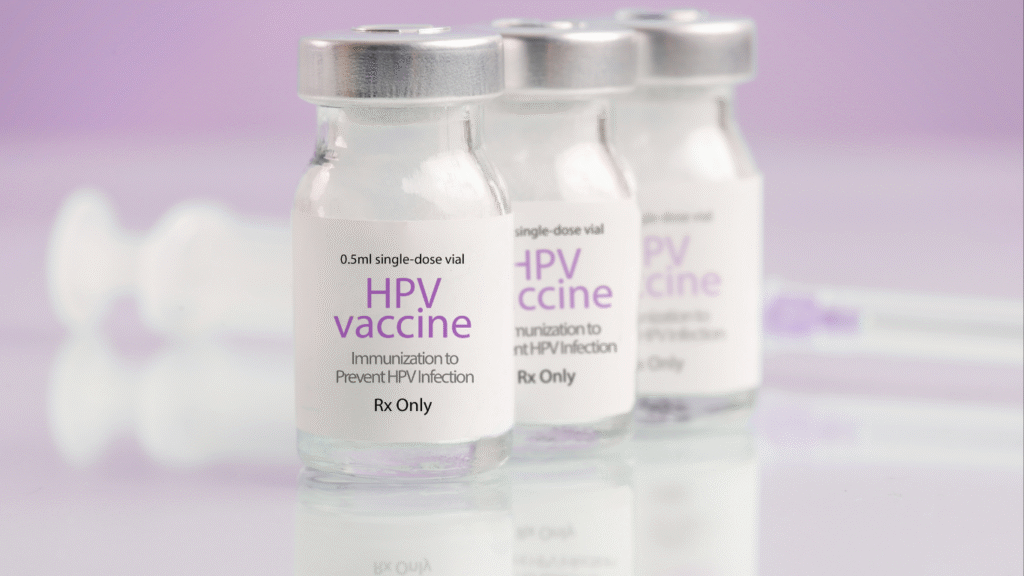

Shope’s discovery was more than just a curiosity. It was one of the first clear demonstrations that viruses could cause tumors. His work opened new paths in cancer research, leading scientists to study other viruses, including my human relatives, and how they might cause cancer in people. Decades later, this chain of research helped inspire the development of HPV vaccines that now prevent countless cases of cervical and other cancers worldwide.

By late afternoon in my human home, I sometimes find myself outnumbered. Immune cells swarm, skin cells shed, and I am carried away, piece by piece. My wart city flattens until the skin is as unremarkable as before. In a rabbit, my keratin towers might still stand, but time and the immune system are patient. Most hosts move on from me eventually.

And yet, I am not easily erased from the world. My particles linger on doorknobs, towels, grooming tools, or the mouthparts of an insect. I wait, dormant but ready, until the next scrape of skin or careless nibble gives me another chance. My world is a web of microscopic doorways, each one an opportunity to start the cycle again.

For humans, prevention is a matter of habits and science. Wearing shoes in public showers, not picking at warts, and keeping skin clean and intact all help shut my doors. For my more dangerous human cousins, vaccination is a shield, blocking their path before they can ever take root. For rabbits, pest control and veterinary care make the difference between a brief visit from me and a more dangerous stay.

Whether I live quietly on a person’s fingertip or stand tall on a rabbit’s brow, I am proof of how small things can weave themselves into big stories. I am part of medical history, part of folklore, and part of the intricate web of life that connects humans, animals, and the unseen world of viruses. And though my hosts may not thank me for the experience, I have shaped their stories as much as they have shaped mine.