Step into the mind of Yersinia pestis, the microbe behind Bubonic Plague. From flea bite to immune battle, discover its journey in a vivid, fact-based story.

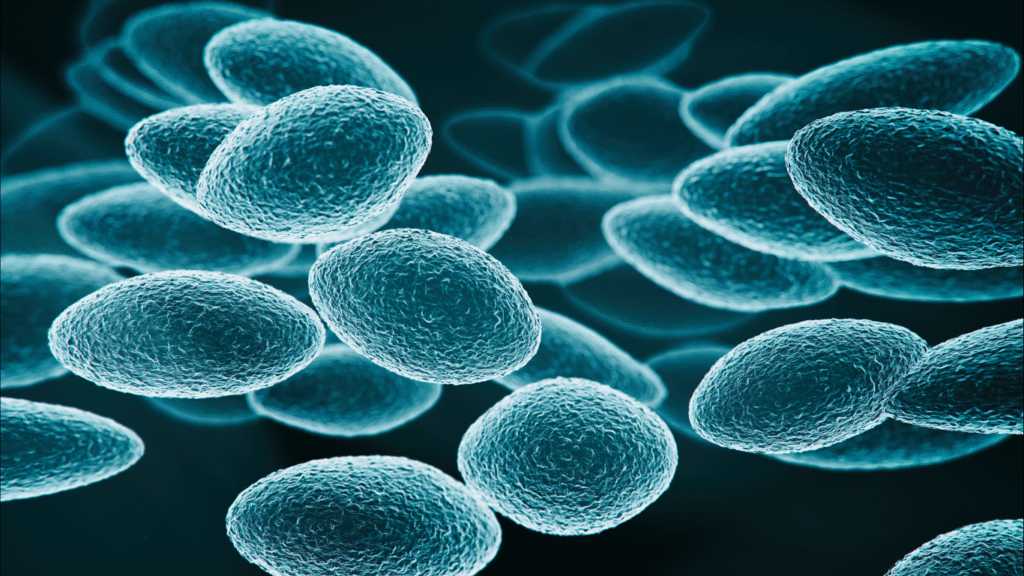

The darkness is my comfort. I rest deep inside the gut of my loyal partner—a flea—nestled among the half-digested remains of its last blood meal. The world in here is cramped, warm, and always in motion. The walls of my little chamber pulse gently as my host twitches and crawls across the fur of a rodent. This is my home, my hiding place, the starting point for everything I am about to do. For countless generations, my kind, Yersinia pestis, has survived this way—traveling in fleas, biding our time until a moment arrives to leap into a new host.

That moment comes without warning. My flea jerks suddenly, feeling the pull of hunger. It leaps off the rodent’s back, landing on warm skin that smells different—less earthy, more human. It bites, and blood rushes into its tiny body. However, because I’ve been clogging my host’s gut with a sticky biofilm, the flea cannot swallow properly. It regurgitates the blood along with me into the bite wound. In that instant, I’m free of the flea and inside a brand-new world. This is how Bubonic Plague begins for most of my victims—through a single flea bite, a process humans have known about since the Middle Ages (CDC).

The wound is small, hardly noticeable. Yet for me, it is a gateway. I drift into the surrounding tissues, moving steadily toward my target—the nearest lymph node. The lymphatic system is like an underground tunnel network, carrying fluid and immune cells all over the body. For a bacterium like me, it’s also the perfect highway. I travel in silence, passing cells that watch for danger but fail to recognize me quickly enough. The clock is ticking, but for now, I have the advantage.

When I reach the lymph node, I begin to multiply. My numbers double, then triple, swelling into thousands. The lymph node itself starts to swell from the chaos. This swelling, hot and tender, is what humans call a bubo—my signature mark. It’s no coincidence that Bubonic Plague takes its name from these painful lumps, which often appear in the groin, armpits, or neck (WHO).

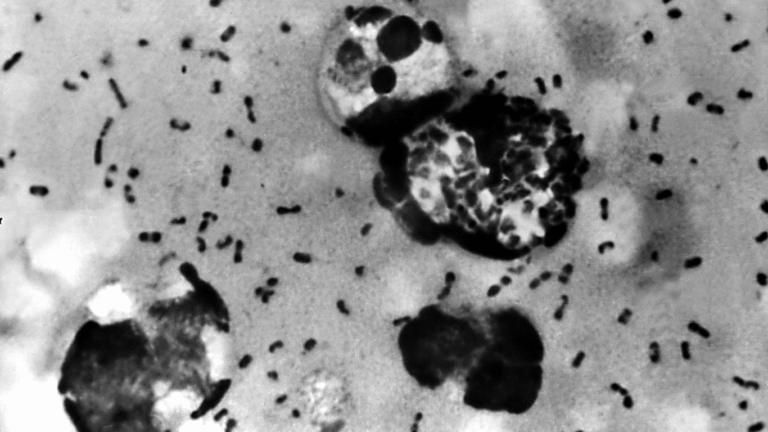

Meanwhile, my host begins to feel the first signs of trouble: fever, chills, headache, weakness. The immune system is mobilizing at last, sending white blood cells to attack me. However, I’m slippery. I can survive inside certain immune cells, hiding from destruction and using them as unwitting vehicles to spread further. Every hour, my population grows, and the swelling in the bubo worsens.

If I stay here, I can cause severe local infection. But if the defenses falter, I’ll slip into the bloodstream. There, my reach extends everywhere—liver, spleen, even the lungs. In some cases, I trigger septicemic plague, which can turn the skin black in patches due to blocked blood vessels, or pneumonic plague, which allows me to spread directly from person to person through droplets (CDC).

Still, not every human I enter is defenseless. In modern times, many live far from my rodent-flea cycle, and even when I do reach them, antibiotics can stop me. Drugs like streptomycin, doxycycline, or gentamicin are my greatest threats. If given within the first day or two after symptoms begin, they can wipe me out completely (CDC).

As I continue multiplying, the immune system grows bolder. Macrophages—large, hungry white blood cells—begin to engulf my companions. Antibodies latch onto my surface, marking me for destruction. Fever rises, a sign that the body is turning up the heat to make survival harder for me. Meanwhile, I can feel the pressure of antibiotics entering the bloodstream, disrupting my ability to function.

On the other hand, in a host without quick access to care, my chances improve. Historical times were my golden age—when humans didn’t understand how I traveled, when they didn’t know to control rodents or fleas, when overcrowded cities gave me endless opportunity. In the 14th century, I swept across Europe in what they now call the Black Death, killing tens of millions. Today, however, my range is smaller, my outbreaks rarer. Still, I persist quietly in rural areas of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, flaring up when conditions are right (WHO).

As hours pass, my host’s condition worsens. Sweating and shaking, they can barely stand. Their lymph nodes throb with pain, and fatigue drapes over them like a heavy cloak. However, modern humans are resourceful. If they suspect Bubonic Plague, they can confirm it quickly with lab tests and begin treatment immediately. Once those antibiotics take hold, my grip weakens. My numbers plummet, my cells rupture, and my genetic code unravels.

Even in my defeat, I am persistent in the environment. My cousins remain in wild rodent populations, carried silently by fleas, waiting for another chance. Humans can prevent most encounters with me by keeping their surroundings clean, controlling rodent populations, and protecting pets from fleas. In areas where I still circulate, avoiding contact with wild or dead animals is a wise precaution (CDC).

By nightfall, my day draws to a close. In one host, I may be gone—destroyed by medicine and the immune system working in tandem. In another, far away, I may just be beginning, injected through a flea’s bite into warm new tissue. My fate depends on how quickly humans recognize my presence and act.

This is the truth about me: I am small, but I am patient. I have traveled through centuries and across continents. I have been a shadow in history’s deadliest pandemics, yet I am also a reminder of how knowledge changes everything. In the days before science, I thrived. In the age of antibiotics and public health, I survive only in the gaps—gaps in awareness, gaps in care, gaps in prevention.

Therefore, the story of Bubonic Plague is not just mine—it’s yours too. Every choice to control rodents, treat pets for fleas, or seek medical care quickly closes the door on my world. Consequently, even though I can hide in the quiet belly of a flea for months, I cannot survive long in a world that is ready for me. And that, perhaps, is the greatest plot twist in my very long day.